Wind Turbines at the Findhorn Foundation

Wind Turbines at the Findhorn Foundation

Findhorn Foundation promotionalism presents a glamorous picture of an alternative organisation offering educational, ecological, and spiritual benefits. The downside of this scenario has been effectively suppressed. The article below presents some of the loss in context that has occurred.

CONTENTS KEY

1. Commercial Workshops, Grof Therapy, and Dissidents

2. The Deceptive Priority of Economics

3. Spiritual Work as Economic Exercise

4. Debt, Business Enterprise, and CIFAL Findhorn

5. New Age Buddhism

6. Trees For Life

7. Dissident Kate Thomas

8. Ongoing Commercial Workshops

During the 1990s, the glowing promotionalism of the Findhorn Foundation depicted a community of great spiritual significance. This was a scenario of personal transformation, the fabled “magic of Findhorn,” healing and channelling, the planetary village, excelling new age education, the “spiritual businessman.”

In August 1993, the Scottish Daily Express reported: “Ex-members talk of terror campaigns and bullying against those who dare question beliefs.” Journalist Ian McKerron was explicit in his informative article New Age Quarrellers. Some occupants of the caravan site had strong complaints.

The frenzied banging on the door signalled terror for Eva Haden. Outside her caravan a man, his face contorted with rage, was demanding entry and bawling he had come to cut off the electricity. Eva, protectively cradling the youngest of her three children, warned she would call the police unless he left. He did, but threatened: “You’re nothing but a troublemaker. I’ll be back.”

The irate and threatening man is described as one of the prominent “spiritual leaders” in the Findhorn Foundation. During an interview, Eva Haden disclosed to the press: “Their claim to be a spiritual community is a complete con. The place is run by a dictatorship. Anyone who steps out of line or questions their rule is subjected to a concerted campaign of harassment and terror.”

Residents of the caravan park were forced out of their homes to make way for the new and expensive “eco-houses” acquired by staff members founding the “ecovillage.” John Montgomery was one of the alienated former members. He told journalist McKerron: “When people come here they give up everything. Then if they don’t conform, the hierarchy simply spits them out and they are left with nothing. These people [Foundation staff] can appear to be full of spirituality, love and caring. But scratch the surface and there is a terrifying viciousness underneath.”

The commercial activity of the Findhorn Foundation was then being run by a Dutch businessman. George Goudsmit represented the company known as New Findhorn Directions. Goudsmit was asked to comment on the complaints of caravan park residents. He admitted to the press that tenants had been threatened with eviction. According to his explanation, tenants were not paying rent. “When you are running a business you have to run it in a business-like manner.”

Tenants complained of broken windows, leaking roofs, and poor sanitation. The caravan park was part of a registered educational charity whose total assets were then estimated (in some directions) to be worth between £10 million and £15 million (some say these figures were inflated). The Findhorn Foundation property included several private houses and a large hotel. Their annual turnover was reported to be in excess of £2 million, derived mainly from course and workshop fees, rents, and sales. Substantial donations had also been incoming.

Dissidents complained that drugs were in common use, despite an official rule forbidding such indulgence.

These details were first covered in Stephen J. Castro, Hypocrisy and Dissent within the Findhorn Foundation, Forres 1996, pp. 76-78 (as a supplement, I possess the author’s collection of press cuttings, documents, and other memoranda from the 1990s).

The people living in caravans complained at a new commercial attitude of the Foundation. An instance was Roan Duzek from Germany. In 1993, she and her two very young children faced freezing December temperatures in a caravan after being refused a £36 gas cylinder on two days credit. Foundation officials used the pretext that their policy was not to allow credit on consumables like gas, “especially for those on low income.”

A former lecturer at York University, Duzek had lived at the caravan park for over three years, saying she had cleared almost two-thirds of her debt in rent payments. Officials complained that she was again getting into debt. Her version was different. A faulty gas fire had exploded in her caravan; injury to her children had narrowly been avoided. She had insisted upon repairs being made to her caravan. However, renovation work was not started until she stopped paying rent. She accused the management of incompetence, vowing to leave the next year. There was a general grievance, at the caravan site, that a popular warden (an amiable Scot) had been dismissed and replaced (“Foundation policy brings cold comfort for mother,” Forres Gazette, 22/12/1993).

At a different Foundation site, the manager of “Education” at Cluny Hill College (in Forres) declared that God had given him jurisdiction. That mandate effectively decoded to the paedophile guru Sathya Sai Baba (d.2011), of whom German staff member Eric Franciscus was a follower. Sathya Sai Baba was believed to be God by his devotees. The “education department” signified alternative therapy, Sathya Sai channelling, and other unconventional approaches. The divine mandate of Franciscus included threatening a Scottish woman with the dire fate of getting “burnt.” Her crime was that of defending a local English female dissident, a victim of defamation by Franciscus and other staff members.

The Scottish woman afterwards had to be rescued from her plight by a retired English GP living in Forres, namely Dr. Sylvia Darke. This medic strongly complained at the abortive persecution of the Scottish victim, who departed from Moray in fear of further intimidation and ill treatment from the Foundation.

The Foundation staff advertised their skill in “conflict resolution,” a popular new age theme. Their lapse was further demonstrated, in 1993, when they subjected a local English dissident to the ignominious fate of cleaning toilets while she was an Open Community member. When the Canadian director of the Foundation afterwards cordoned this victim, the membership was declared non-existent via an elaborate ruse. All the negative manifestations of “Education” were consigned to oblivion. The unwanted details were preserved only in dissident and critical literature. The misleading partisan literature extolled the Findhorn Foundation as “a community demonstrating a way of life in conscious co-operation with God.”

During 1994-95, the Foundation staff demonstrated an extremist attitude of hostility to schoolteacher Jill Rathbone. As a consequence, she lost a new post with the local Moray Steiner School, for which purpose she had moved from distant Cambridge (UK). The strong Foundation influence upon the Steiner School resulted in a legal case and manifest indifference to the law. The School "refused to accept the original serving of the writ issued by the local Sheriff of the law courts, who, therefore, intervened by freezing the monies of the Steiner School by public ceremony at their local bank" (Castro 1996:167). The Foundation advisors clearly felt they were above the law.

Rathbone subsequently won the case, only to be further snubbed by preening Foundation staff, who claimed the cause of dispensing "unconditional love." Her major persecutor was an American staff member. In 1995, this man "focalised" a neo-shamanism workshop entitled The Gentle Warrior. The promotion here stated: "We can learn to stand for the power of gentleness, kindness, compassion, and love." The charge was £300-400 for a week (Castro 1996:187). This particular staff member was notorious for intimidation, both within and outside the Foundation. Lip service to platitudes was extensive.

The Foundation had incurred a heavy debt when they declared NGO status in 1997. Widespread puzzlement occurred as to how this distinction was acquired. The prominent Scottish politician, Dr. Winifred Ewing MSP, proved unable to obtain a response from the New York offices reported to confer the NGO status. European offices of UNESCO subsequently disowned any NGO associations in relation to the Findhorn Foundation, this disclosure being made to a British MP, namely Robert Walter. Persons of lesser profile were unable to gain replies from any UN offices in Europe, including the celebrated UNITAR, who chose to confer CIFAL status upon the disputed organisation in 2006 (a status ending in 2018, when the related business company was dissolved).

1. Commercial Workshops, Grof Therapy, and Dissidents

The Findhorn Foundation has presented an anomaly to close observers. That community, acquiring NGO status in 1997, have promoted themselves as a centre for spiritual education and “transformation.” During the 1990s, they established the Findhorn ecovillage, a project existing on the same territory as the Findhorn Foundation. There is no effective distinction.

In 2006, UNITAR endorsed what became known as CIFAL Findhorn Ltd. This was at first identified as the twelfth CIFAL centre worldwide, existing for the purpose of ecological training programmes associated with the United Nations. The glowing promotionalism for CIFAL Findhorn Ltd was prodigious. This enthusiasm is viewed as exaggerated by critical observers. After five years, CIFAL Findhorn Ltd became CIFAL Scotland Ltd. The national business logo did not prevent that enterprise from terminating in 2018, after a substantial reduction in the numbers of personnel. Moray Council had strongly supported the promotionalism and offical appointments, a particular interest being awarded to benefits of tourism.

Close analysis of attendant events revealed some disconcerting factors. For one thing, the ecological declarations existed side by side with the commercial workshop programme of the Findhorn Foundation. This activity provided an ongoing means of income for many years, giving support to many alternative therapists and other entrepreneurial entities associated with “new spirituality.”

The doubtful agendas incorporated in the “workshops” are sold for noticeably high prices, catering for an international clientele. The promotionalism for this long established programme strongly encourages an uncritical approach to the themes and practices being sold. These workshops and courses frequently last for a week or so, costing on average several hundred pounds, the fee varying somewhat.

The commercial workshop programme has nothing to do with ecology. Critics dispute that this programme should be described in terms of spiritual education. The scenario amounts to an entrepreneurial form of fashion in “alternative” concepts. The format of the workshop programme bears strong resemblances to commercial schedules maintained by the Esalen Institute in California. Since the 1970s, the Findhorn Foundation has received many American guests, who transmitted the “alternative” conceptualism emanating from California.

Prior to the 1970s, the nascent Findhorn Foundation was under the more exclusive influence of Peter and Eileen Caddy, whose situation on a caravan site caught the imagination of the late 1960s “new age” trend in Britain. See Myth and Reality. During the 1970s, the Foundation commenced a phase of expansion via property acquisition. Cluny Hill College in Forres became a key venue. However, conventional standards of education did not apply. That college was run as a centre for alternative therapy and related trends. This situation was glorified in terms of the so-called “holistic” experience claimed by the Findhorn Foundation.

There were other problems also. The Foundation acquired a severe economic deficit during the 1990s. The persistent attempts to conceal this flaw lapsed in 2001, when a debt of £800,000 was publicly declared. Elaborate measures were taken to offset this drawback, including a proliferation of business enterprises that were nominally independent. The trend continued with CIFAL Findhorn Ltd, also conducted as a separate business from 2006. Close inspection of the community under discussion is similar to charting a business combine with different faces all having the same head.

While under the long shadow of undeclared economic malaise, the Findhorn Foundation became an NGO in 1997. Exactly how they achieved this became a matter for local speculation. They were deriving income from dubious commercial workshops, even while accumulating a debt that soon led to the mortgage of Foundation properties. The Findhorn Foundation College was born amidst the overdraft anomalies, being another exercise in holistic claims that are deemed superficial elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the fabled “eco-houses” were appearing in the new "ecovillage." The price of these dwellings became expensive. Local analysts said that only affluent persons could afford the luxury abodes. The ecovillage was also run on business lines; there is no doubt that profits were involved for the entrepreneurs. However, the promotionalism gave the impression of an ecological utopia deserving of UN patronage.

Dissidents were unwelcome to the point of exclusion. In 1996, only a year before the acquisition of NGO status, a book was published in Forres that aroused the wrath of the Foundation staff. The welll documented dissident book was unofficially banned via elaborate denials. Vistors were told repeatedly not to read this annotated book, endorsed by ICSA in a very different environment. The Foundation staff blockade was confirmation of the unyielding managerial attitude to dissident views and complaints. Democracy was something generally assumed within the Foundation, but in practice was a long way off. The reality did not match the sentiments in vogue.

l to r: Stephen Castro, Craig Gibsone |

The dissident book was entitled Hypocrisy and Dissent within the Findhorn Foundation. The author was Stephen Castro, a resident of Forres who had for seven years witnessed the discrepancies prevalent in the expanding community commenced by the Caddys in 1962. This annotated work contrasted with the enthusiast literature favoured by the management, whose publishing arm set great store in simplistic partisan accounts and the “God Spoke to Me” output of Eileen Caddy.

Hypocrisy and Dissent reveals an authoritarian regime who were customarily evasive on the subject of local dissidents. Trustees, management, and staff were all dismissive of problems on their doorstep, contradicting their constant claim of expertise in conflict resolution. Above all, the hierarchy could not accept criticism of their policies, even when such policies involved blatant injustices. The favoured recourse was suppression and stigma. This was the new age of “holistic” achievement and entrepreneurial “spirituality.”

The Castro book met two distinct fates. In 1996 this volume was favourably reviewed by ICSA, being recognised by some academics as a valid stand against bad management and dictatorial strategy. Within the Foundation however, that book was continually maligned. This situation assisted a dismissive internet stigma of 2002. The Foundation management chose to favour a statement, from a zealous supporter, that the dissident book was “not worth reviewing.”

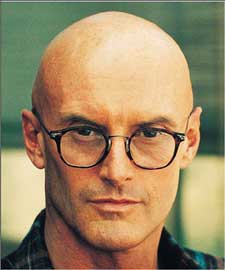

Stanislav Grof |

Chapter six of Hypocrisy and Dissent is particularly relevant to the commercial workshop programme of the Foundation. This chapter describes events attendant upon the sponsorship of Grof Transpersonal Training Inc. That commercial activity gained a strong foothold within the community during the years 1989 to 1993. Stanislav Grof was a former prominent resident of the Esalen Institute, where he had improvised Holotropic Breathwork as a lucrative therapy. Grof was also an influential advocate of LSD "therapy," which had become illegal.

Grof had undertaken thousands of LSD sessions. He was furthermore actively involved in the pursuit known to partisans as MDMA “therapy.” This indulgence became illegal during the 1980s. MDMA is popularly known as “Ecstasy.” Grof remained a staunch partisan of the drugs LSD and MDMA. Despite this disconcerting psychedelic factor, he was celebrated at the Findhorn Foundation as an expert in psychology and spirituality.

At the Foundation workshops, Holotropic Breathwork was observed to create serious problems for some clients, including “screaming, vomiting, hysterics.” Hallucinatory experiences were also evoked, plus unpleasant aftermath symptoms such as disorientation. The management were strongly resistant to due criticisms of the Breathwork, especially as the Foundation Director (Craig Gibsone) had become a practitioner of this exercise in hyperventilation.

Holotropic Breathwork was eventually suspended due to a recommendation from the Scottish Charities Office, which in 1993, duly acted upon a negative report from the Pathology Dept of Edinburgh University. Despite the official warning, Craig Gibsone and other Foundation personnel subsequently perpetuated the controversial therapy in a “workshop” setting. This tendency aroused complaints. Gibsone became a leading celebrity of the "ecovillage," a project emphasising sustainability, to the accompaniment of heavy debt and many air flights causing pollution.

Kate Thomas |

A major critic of Holotropic Breathwork was Kate Thomas, a local dissident and eyewitness who was effectively outlawed by the Foundation management. She was proven correct in her reservations concerning Grof therapy. Instead of duly conceding this factor, the Foundation hierarchy continued to stigmatise her for independent views. They created acute distortions of her complaint at their unjust policy in her direction. Their tyranny is indicated by a document of Kate Thomas, which the Foundation typically ignored. See the Letter of Kate Thomas to UNESCO (2007).

Civilised responses to the Letter to UNESCO were of a different kind entirely. A copy was despatched to the Hon. Tom Sackville, Chairman of FAIR, who sent a sympathetic reply dated 1/10/2007. Sackville transpired to be critical of the Findhorn Foundation. A former MP, Sackville was previously an official in the Home Office; he had become very critical of British government lethargy in relation to malfunctioning organisations. Acting upon advice from the Chairman of FAIR, Thomas subsequently contacted her local MP, who proved sympathetic to her case (section 7 below).

Problems such as Grof therapy were continually missing from the Findhorn Foundation publicity tactic. Critics refer to ongoing Foundation promotionalism and “workshops” as a form of miseducation, causing widespread confusion amongst susceptible subscribers. Such matters are treated at more length in Findhorn Foundation Commercial Mysticism. See also Kate Thomas and the Findhorn Foundation.

2. The Deceptive Priority of Economics

In 2006, complaints were addressed to UNITAR about the proposed CIFAL centre in Moray. The suitability of the Findhorn Foundation, as the location for this public service training centre, was strongly contested by three critics of the Foundation, including a retired accountant living in Scotland. There was no reply from UNITAR, a fact which caused further alarm. Official plans and decisions evidently considered public complaints irrelevant.

An elaborate screening process was in occurrence. The major fulcrum for this was Moray Council, who had recently decided that economic prospects were strong in relation to the newly proposed CIFAL centre. That council refused to acknowledge a circular of complaint despatched to relevant persons in June 2006. Moray Council were anxious to push through the new plan without any obstruction to their aims. In September 2006, they gained success by finalising the scheme for CIFAL Findhorn Ltd, in collaboration with UNITAR and the Findhorn Foundation. The local Forres newspaper reported that a “deal” had been signed in Geneva between those three parties.

UNITAR is the abbreviation for United Nations Institute for Training and Research. That organisation, based in Geneva, are accused of inadequate research into the Findhorn Foundation, who were glorified by official strategies ignoring public complaints.

Reference here to certain correspondence of 2007 is pressing. John P. Greenaway wrote a letter, dated 26/03/2007, to Nicol Stephen MSP. This communication gave relevant information about matters relating to the Findhorn Foundation and the UN. In March 2006, the prospective CIFAL project was promoted in the local press of Moray, subsequently receiving a supporting majority vote from Moray Council in the ratio of 13-5. Later, the anticipated construction of a £1 million CIFAL training centre was formally announced (and much embellished in some reports, reference to a multi-million pound project being encouraged by propagandists).

In the face of this official support, Greenaway and other critics had pointed out the disparity involved in a significant accounting discovery: “For well over a decade, the Findhorn Foundation, a registered charity, has been running a covert fund, probably mostly invested in property, for the benefit of its leading affiliates. This amounts to approximately £1 million, over and above its publicly revealed assets of £2 million approx.” Greenaway continues: “I am informed that, back in 2002, this analysis was accepted by the Financial Services Authority in London, but the FSA did not have the power to act.”

Winifred Ewing MSP |

Furthermore, “widespread local negative perceptions of the Findhorn Foundation were reported to Dr. Winifred Ewing [MSP], who was a parliamentary representative for Moray for 29 years until her final retirement in May 2003." In 2002, Dr. Ewing alerted three other parliamentarians who were billed to speak at Foundation conferences. She informed them that the true state of affairs included financial irregularities, exploitive prices, extensive deceit and manipulation, and the dangerous ongoing therapy known as Holotropic Breathwork.

Those three politicians then decided not to attend the conferences. Their identities were Rhona Brankin MSP, Michael Meacher MP, and Mo Mowlam MP. Greenaway adds that Dr. Ewing never changed her mind about the organisation under discussion. She was still writing on that subject in 2006, admiring the perseverance of a critic like himself.

Both Westminster and Holyrood failed to act on the critical medical reports available about Holotropic Breathwork (HB). Although that high risk “therapy” was dropped from the Foundation programme in 1994, HB continued to be dispensed on a private basis in defiant sectors of this organisation. Furthermore, a group of influential Foundation personnel “began to conduct annual HB workshops every autumn” at the Foundation-associated venue of Newbold House in Forres.

This defiance of medical warnings continued until 2005, after which renewed official concern acted as a deterrent. The key HB presenter was Craig Gibsone. Discrepantly however, he and his wife were described as “the leading link throughout between the Findhorn Foundation and the UN, mostly via Dr. Pierre Weil in Brazil” (Greenaway epistle cited). The anomalies and lunacies of this situation have been obvious to critics. Pierre Weil gained the reputation of an eccentric new age innovator remote from medical science; he founded the Holistic University, which does not represent mainsteam education.

Greenaway dates to circa 1996 the Foundation process of revamping into smaller units. The trend of apparently independent projects “disguises connections with the parent body, and makes it easier for Foundation connected concerns to successfully apply for Scottish Executive or EU grant aid or Lottery money" (epistle cited). This trend has been described as an economic deception.

The same informant raised the question of why Scotland could not run a national ecological training centre, either alone or in partnership with England, thus bypassing the Findhorn Foundation problem. The relevant letter was mediated via Nicol Stephen to a presiding official.

Michael Russell MSP |

The Scottish Minister for Environment, Michael Russell MSP, sent a response to Nicol Stephen MSP dated June 2007. To quote here from that letter:

Your constituent expressed concern about the suitability of the Findhorn Foundation as the location for a public-service training centre and asks why Scotland cannot run its own, similar centre. Decisions on the location of CIFAL centres rest entirely with the relevant UN agency having due responsibility for training issues, namely UNITAR, and it is to them that your constituent should address their concerns in the first instance. The Scottish Executive welcomes the establishment of the centre in Moray, and both the Moray Council and Highlands and Islands Enterprise Moray are supportive of the development of the CIFAL centre. Indeed, HIE have assessed that a CIFAL facility located in Findhorn has the potential to bring additional economic benefits to Moray over and above those they have identified as flowing from the Findhorn Foundation.

This quotation demonstrates something of what critics had been complaining about and still are. There was no recognition by the Scottish Executive of prior events or compromising features. The assessment in terms of economic benefit remains shallow and unconvincing to those with a larger compass of information than is afforded by bureaucratic convenience. The shallow pursuit of economic interests is an ingrained feature of contemporary politics, one that so frequently curtails due educational data, creating confusion about priorities.

Michael Russell also referred to concerns about accounting practice which had been raised in relation to the Findhorn Foundation. The mode of dismissal is here memorable:

I am not aware of any irregularities in accounting practice which give grounds for concern. I note also that HIE (Highlands and Islands Enterprise) Moray has been made aware of these concerns in the past, and by the correspondent’s own admission responded to the effect that a copy of a critical analysis of accounting practices at the Findhorn Foundation was not relevant.

Was anything here being unduly dismissed or uninvestigated? According to critics, the political support for economic interests had seriously obscured the record.

The constituent referred to, in the above-quoted letter, was the author of a book on the Findhorn Foundation, a man closely familiar with many events in the far north, being an inhabitant of Aberdeen. John Paul Greenaway gained a degree in law at Hull University, later becoming a civil servant. He had intermittent contact with the Findhorn Foundation during the years 1974-1992, and is classifiable as a dissident. He wrote an informative reply to letters from Nicol Stephen, the MSP for Aberdeen South. The major Greenaway epistle, dated 16/09/2007, was in disagreement with some statements made by Michael Russell MSP in the above-quoted letter.

Marcel Boisard |

Greenaway reiterates, in his epistle to Stephen, that he had in fact addressed his concerns to UNITAR, and more specifically, to Marcel Boisard, the Executive Director of UNITAR. His lengthy letter of July 2006 to Boisard had not gained any response. To make quite sure of receipt, Greenaway had even sent a follow-up copy, which likewise did not receive acknowledgment.

Furthermore, a retired accountant of Moray had submitted to Boisard a copy of a significant analysis of Findhorn Foundation accounts. “This reveals a £1 million hidden fund, verified by the FSA (Financial Services Authority) in London.” The accountant was named in the letter to Nicol Stephen, but otherwise wishes to remain anonymous. That accountant had sent a covering letter to Boisard, along with his analysis. Disconcertingly, there was again no reply, not even an acknowledgment. The analysis of accounts was also sent to Nicol Stephen, who had duly responded.

Greenaway also mentions that a third communication was sent to Boisard, this time from myself, and one receiving exactly the same indifferent treatment. In fact, Boisard was a major recipient of my Letter to the Home Office – About the Findhorn Foundation and UN (2006). That lengthy circular achieved two versions, the first being despatched to the Home Office, and the amplified sequel having a cc. list including many members of Moray Council. The latter contingent notably furthered the tactic of evasive non-response for which UNITAR is now notorious in Britain. See Letter to the Home Office.

The epistolary account of Greenaway supplies important details ignored by the Scottish Executive and their commercial inspirers. He starts with the significant detail that in 2002, Dr. Winifred Ewing MSP had written to the Dept of Public Information (DPI) at the UN headquarters in New York. The Findhorn Foundation continually invoked the DPI as a source of legitimation. Dr. Ewing accordingly requested information from the DPI as to how the Findhorn Foundation had managed to obtain the various UN affiliations that were commercially advertised. Dr. Ewing received no response from the DPI, indeed not even a formal acknowledgment of her very relevant enquiry.

The convergent negligence, in communications protocol, of the DPI, UNITAR, and Moray Council has aroused comment. The failing has been described in terms of the deficient apparatus of a semi-literate and high-handed bureaucracy whose decisions and mandates are in very strong query. However, that reflection does not appear in the Greenaway epistle, which maintains polite format throughout. Greenaway does, however, make the pertinent point that UNITAR policy resembles a “bureaucratic autocracy” in the absence of a more desirable regulatory procedure which should “take soundings from the local and broader community.”

Winifred Ewing MSP |

Dr. Winifred Ewing was a parliamentary representative for Moray and the Highlands for 29 years until her retirement in 2003. Her complex political career commenced in 1967. She was the first female MP in the Scottish National Party, acting as President of the SNP during the years 1987-2005. In May 1999, she chaired the first session of the Scottish Parliament.

Dr. Ewing had a senior position to Angus Robertson MP and (the late) Mrs Margaret Ewing MSP, both of whom are associated with furthering the CIFAL Findhorn project in nascent stages. Greenaway urges that Robertson and Margaret Ewing failed to communicate to UNITAR the strong reservations of Dr. Winifred Ewing about the Findhorn Foundation. Margaret Ewing (d.2006) was the daughter-in-law of Dr. Ewing, and MSP for Moray.

Greenaway refers to his lengthy conversation with Dr. Ewing at her home in January 2002. She then told him how she had received “innumerable complaints” about the Findhorn Foundation, over the years, from her constitutents. She also expressed her own strong aversion to the Foundation, based upon reports and experiences. Greenaway also states that he has “a considerable file of letters from Dr. W. Ewing through nearly four years which substantiate her view.”

Grievances have arisen over the enthusiastic and uncritical sponsorship of the Findhorn Foundation by two relative newcomers, namely Angus Robertson MP and Richard Lochhead MSP. The point is made by Greenaway that if Dr. Ewing had been consulted, the CIFAL project in Findhorn could not have gone ahead with any due justification. The changes in local opinion were attributed to the activities of Robertson, strongly implied as a convert to Foundation ideology, being in close association with controversial Foundation celebrities.

Greenaway strongly questions abilities of assessment in the support faction for the Findhorn Foundation. To quote from his letter:

Where in the array of support for this CIFAL Centre is there anybody (a) with accounting qualification up to Chartered Accountant or equivalent? (b) with long years experience of accounting, particularly in the use of techniques for detecting fraud? (c) who, possessed of a and b, has actually examined the Findhorn Foundation accounts, as Mr. -------- has done? [This reference is to the accountant in Moray]

Greenaway informs that what has been proffered instead, by Findhorn Foundation supporters, is “the ludicrous ‘Economic Impact Assessment’ (EIA) commissioned by HIE (Highlands and Islands Enterprise), by an ‘economist’ about whom we know nothing, including nothing about his prior relationship with the FF and its conditioning workshops (examined in several book exposes). This so-called ‘EIA’ is full of implicit value judgments which are political in nature.”

The HIE has been described as an economic development agency of the Scottish Government. There have been reservations however. The Moray branch acquired a poor reputation amongst critics. That situation was not remedied when, in 2003, the HIE Chairman refused to provide the professional accountant in Moray with a copy of the full EIA. This accountant was the same man whose analysis was accepted by the Financial Services Authority in London.

Greenaway further comments:

So much for the ‘open government’ as interpreted by HIE! Behind a smokescreen of fashionable terminology, HIE are still stuck in the old ‘sub rosa’ groove. HIE has made only a shortened version of this EIA available to the public.

Suspicions attaching to the maneouvre known as Economic Impact Assessment (dating to 2002) are pronounced, implying an instance of the propagandist tendency noted to be at work in the Findhorn Foundation for many years. Glowing portrayals of Foundation expertise and achievement have invited strong repudiation from those well informed about the internal tactics of Foundation celebrities and their ideological agenda.

Following up his critical reservations, John Greenaway provides significant information. He asks in his letter: “What is ‘support’ from Moray Council and HIE worth?” The answer he supplies is relevant to quote here in full:

On Feb. 8, 2006, ‘Audit Scotland,’ an official body of the Scottish Executive, issued a damning report on the general competence of successive Moray Councils through the period 1996-2004 (I have given some further detail on page 7 of my letter to Mr. Boisard, UNITAR, copied herewith). In August 2007, as reported in local Moray Press, Audit Scotland stand by their damning assessment. HIE, and particularly its local Moray version, has not been a respected organisation either. Please see my account, on pp. 5 and 6 of my letter to Boisard, of serious criticisms of HIE from economist Tom Mackay, and from EU auditors.

It is reasonably evident that discrepancies in the CIFAL Findhorn project were sufficient to arouse strong caution, meriting critical scrutiny rather than facile acceptance. A further reason for caution was the fluency of tactic on the part of politicians.

Nicol Stephen MSP duly reported to Michael Russell MSP the substance of concerns raised by John Greenaway. Russell replied to Nicol in a letter dated November 2007. That reply was rather more guarded than the former commentary from the Minister for Environment, but considered disappointing by critics of the Findhorn Foundation. After three opening lines of formality, the second and final paragraph read as follows:

I have little to add to my reply to you from June this year about previous correspondence from Mr. Greenaway in which he raised a number of concerns in connection with the training centre at Findhorn. The matters which Mr. Greenaway raises are ones which he would be best advised to pursue directly with those to whom his points are addressed, namely UNITAR, the local authority and enterprise company, the named individuals in his letter, and the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator. I note that Mr. Greenaway has already taken steps to contact some of the parties mentioned above, and while it is unfortunate that he has not received a response to his questions, that approach would appear to be the appropriate course of action.

Commentaries on this episode should be duly critical of the Scottish Executive. The “appropriate course of action” is so often contradicted in contemporary British political circles. Excuses for sanctioning inappropriate situations are too frequently improvised. Critics say that too many politicians and bureaucrats make the wrong decisions at the public expense. All that really counts, in too many cases, seems to be economics and salary, which has been the basic pursuit of the Findhorn Foundation managerial elite, to judge from much of the data afforded.

It proved impossible to elicit any response from UNITAR, whose degree of irresponsibility towards British public complaints is not admirable. In another direction, the local authority (Moray Council) and enterprise company (HIE) in Moray are still regarded as a joke by critics. Nor does OSCR (Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator) command any deep respect amongst close observers. Greenaway referred to this administrative body in his informative epistle to Stephen cited above, asking what had happened to the formerly envisaged investigation of Findhorn Foundation accounting by OSCR. Greenaway states that Investigations Officer Thomas Thorburn, of Dundee, had commenced such an investigation, “acting under new powers emanating from the new Charities (Scotland) Act.” Greenaway asked if this investigation had ceased, and if so, why? He learned that due investigation amounts to a blind alley in sectors where misinformation is rife.

OSCR communication was less than perfect. In my own case, an exchange of letters in 2006 with Senior Investigations Officer Thomas Thorburn confirmed that the Findhorn Foundation had categorically denied hosting Holotropic Breathwork in recent years. This denial was transparent as a facesaver, even to indifferent parties. OSCR did not follow up relevant cues, instead failing to reply to the second letter I sent to Thorburn dated December 2006.

Thus, OSCR also fell in line with the precedent of evasion set by the Findhorn Foundation and UNITAR. The new Charities and Trustee Investment Act 2005 was effectively meaningless in bureaucratic situations of inertia. See Letters to Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator.

The eagerly awaited (and fantasy creation) multi-million pound CIFAL centre at Findhorn never materialised. The exuberant propaganda gradually decreased from the Foundation and their key ally Moray Council. Observers wondered why CIFAL prestige amounted to a business company. Moreover, after five years, CIFAL Findhorn Ltd changed name to CIFAL Scotland Ltd. Critics interpreted this identity switch in terms of an attempt to make the project seem more nationally important. The bid failed. The project lost personnel, eventually terminating in 2018 after most of the officiants had resigned.

Moray Councillors were active as members of CIFAL Findhorn Ltd and the sequel company. Financial dividends were not high for the seminars and courses involved in this charity. The e-learning packages increased course-related income. However, there was reference in 2014 to a UNITAR affiliation fee of £13,800. The Scottish government funded a related project in Bangladesh, more in line with CIFAL objectives than ambitions of the tourist trade and "workshop" industry. In the delta area of Bangladesh, communities were in danger of salt water inundation from tidal rivers. Who really cared about the poor in Asian countries, or what ecological damage actually amounted to? Only balance sheets were exciting to "spiritual businessmen," an underlying factor of Foundation activity. In relation to UNITAR, the spiritual business ground to a halt by 2018, while continuing in other guises such as the Game of Transformation. The celebrated deal at Geneva, in 2006, did not prove viable.

During the intervening twelve years of associated CIFAL status, the Foundation gained many more gullible subscribers. These people were led to believe that ecovillage commercial "workshops" were a divine asset and proof of co-creation with God, confirmed by CIFAL prestige.

Moreover, in 2009, the CIFAL camouflage attended a deceitful ploy achieved by the Company Secretary of CIFAL Findhorn Ltd. John C. Lowe assisted the Foundation manager to deny known membership details of a victim who launched a legal complaint. The Foundation officiants here avoided all accountability. John Lowe was simultaneously secretary for the Foundation and the secretary of CIFAL Findhorn Ltd. The resort to a lie means that "CIFAL here denoted dishonesty and dissimulation" (Vatican of the New Age).

3. Spiritual Work as Economic Exercise

The Scottish Executive effectively buried the accounting anomaly discussed above in relation to the Findhorn Foundation. However, that matter did receive published mention in my book Pointed Observations (2005), pp. 383-85, note 175. The relevant document was entitled A Financial Appraisal of the Findhorn Foundation, accepted by the Financial Services Authority in London. “The details pertain basically to the 1985-95 period, though with some reference to the few years succeeding.”

The disconcerting details, relayed by A Financial Appraisal, include a disclosure made in 1992 which provides a significator of the general trend. The Foundation then admitted that the net worth of their company known as New Findhorn Directions (NFD) had fallen from £99,100 to £21,000. The Foundation is said to have increased loans to this company as the danger of insolvency increased, a fraught situation implying that NFD directors risked the potential loss of savings deposited by their adherents. The Financial Appraisal urges that such measures would normally be considered a misuse of funds.

The same document duly states that “the entire management team resigned” after the Findhorn Foundation profits had dwindled significantly between 1995 and 1997. The new management team likewise failed to stop the escalating debt. All such details were omitted by official sponsorship of the controversial community, who spelled deceptive “economic benefits” to political parties in strong contention.

The Financial Appraisal names the members of the new management team who took ineffective “control” in the late 1990s. The three most well known of these personnel are Alex Walker, Eric Franciscus, and Robin Alfred.

Alex Walker |

Alex Walker is strongly associated with New Findhorn Directions, having become the managing director of that enterprise. He insisted that “a major task is to marry business and spirituality,” a theme evocative of the “Spiritual Businessman” role attributed to Francois Duquesne, the Foundation leader in the early 1980s after the retirement of Peter Caddy (Carol Riddell, The Findhorn Community, 1991, pp. 223, 269ff., 88-9). Walker cultivated the long-term profile of a management consultant.

Published in 1994, Alex Walker’s edited work entitled The Kingdom Within served to screen out the ongoing economic deficit, providing a glorifying view of the Findhorn Foundation, indicated by the sub-title A Guide to the Spiritual Work of the Findhorn Community. The consequences of “Spiritual Work” and “Spiritual Business” led to the declared debt of £800,000, a very big deficit for such an alternative community as the Findhorn Foundation, which began life on a caravan site in the 1960s. The debt was not declared until 2001, by which time it was obvious that the new management team had failed.

The presumed “spiritual work” is viewed by critics as an exercise in economic gains and losses. The insidious promotionalism, encouraged by Walker and other Foundation celebrities, has presented the Findhorn Foundation in such glowing terms as “demonstrating a way of life in conscious co-operation with God.” Another exalted description, favoured by this organisation, was “a centre of spiritual service in co-creation with nature.” A description favoured in 2005 was “a centre of spiritual education.” An elaborate promotion of NGO status was in accompaniment, associated with the UN Department of Public Information, repeatedly invoked over the years by the “intentional community” at Findhorn. In 2009, the Foundation described themselves as "a unique spiritual community."

Kate Thomas |

Taking cover behind such elaborate designations, the Findhorn Foundation have continued an extremely evasive policy in relation to dissidents and critics, who do not exist in the high-flown surfeit of glowing partisan descriptions. The case of Kate Thomas is particularly graphic (section 7 below).

The mood of evasion proved contagious. Eric Franciscus was one of the management personnel notorious amongst dissidents. He gained the reputation of a dictatorial bully. His very revealing conversation with the dissident Kate Thomas is preserved intact on a tape recording dating to 1994. The verbal and behavioural excesses of Franciscus were amongst the drawbacks mentioned in a critical account submitted, in the form of a complaint, to another organisation closely associated with the Findhorn Foundation.

The so-called Scientific and Medical Network (SMN) are known to have encouraged the assimilation of Findhorn Foundation subscribers and concepts, especially via the Wrekin Trust [and the failed University for Spirit Forum], a body which is likewise intimately related to David Lorimer, an impresario of "alternative" conferences and workshops.

David Lorimer |

My document entitled Letter of Complaint to David Lorimer (2005) was sent out as a circular in 2006. That was a fairly lengthy epistle. Lorimer failed to reply, as did all but one of the other SMN members specified in the cc. list. Observers grasped that the Findhorn Foundation meant a source of revenue to the SMN, an economic priority precluding any ethical consideration. The SMN are an “alternative science” organisation whose performance is handicapped by an indifference to pressing matters of scruple.

Lorimer and other members of the SMN were enthusiastic about themes like “near death experience.” Critics say that such themes are no excuse, or justification, for failure to extend due responses in the epistolary dimension. There are too many pastimes of exchequer value in the activities and outreach of such evasive organisations.

4. Debt, Business Enterprise, and CIFAL Findhorn

Long before 2001, the Findhorn Foundation had failed dismally in their proclaimed economic prowess. The replacement management team at first gave the impression that the problems had been rectified. A superficial strategy preserved the propagandist image of inviolability. NGO status was achieved in 1997, an event remaining in strong question.

Local observers, like Dr. Winifred Ewing MSP, were very sceptical. How had the NGO distinction been achieved? The details were very difficult to penetrate. Smooth promotionalist jargon gave the impression that NGO status was a natural outcome of great holistic achievements. The economic malaise was carefully concealed from public view. The UN Department of Public Information became the major publicity prop for the imagined prowess that was effectively bankrupt and so heavily supported by donations.

In 2001 the duplicit image was shattered. The extensive debt of (at least) £800,000 was now impossible to conceal. This would represent a small sum to a large organisation. However, the Findhorn Foundation had never become an economic giant. Lost to open view, though well known to dissidents, was the influential factor of an increased salary structure so very much desired by the new “executive” personnel. In former times, the Foundation staff had lived on pittances, a dearth possibly more suited to their proclaimed spiritual expertise that was doubted by critical observers.

Director Craig Gibsone changed this situation irreversibly at circa 1990. Not only did Gibsone tenaciously sponsor Grof Transpersonal Training Inc., he also wanted an income more resembling the Grof purse than anything evocative of renunciate values. Gibsone, who toyed with Mahayana Buddhism, was never a world-renouncing monk.

Dissidents stated that the economic malaise was in part caused by the desire of Foundation staff for increased salaries; these innovations soaked up funding. Increases were consonant with the capitalist agenda of such an influential management consultant as Alex Walker. In this calculating atmosphere, the hapless communal assets of the Findhorn Foundation were privatised during the 1990s. Such factors contributed to an axis of operation in no way different from the prevailing capitalism of the outside world. The sphere of “spiritual business” was geared to balance sheets, revenues, donations, plus the annual commercial programme of misleading “workshops” in pop-mysticism and alternative therapy.

Findhorn Ecovillage |

Another form of commercial activity was invented in the form of “eco-houses.” Critics describe this subject as being invested with elaborate mythologies serving to conceal too much of what was really happening. The “ecovillage” concept can easily be distorted and abused. In 1997, the neighbouring territory known as Dunelands was purchased by a number of Foundation members. This new acquisition of land adjoined the location known as The Park (near Findhorn village), where the Universal Hall was situated. The investors made the most of this expansionist opportunity.

Even some Foundation members were puzzled by the soaring prices of “eco-houses” over the years. Yes, these dwellings certainly did have features that can be identified with the ecological incentive. However, they were also part of a commercial trend catering to affluent subscribers. People who purchased eco-houses tended to want a substantial return upon resale. There were over fifty of these dwellings by 2010, varying from the basic "barrel houses” to rather more elaborate abodes compared to a luxury housing estate. While simplicity is an apparent keynote of the former, a degree of affluence hallmarks the latter. The days of low income caravan tenants were over.

Commercial overtones of the Foundation buzzword “sustainability” became notorious amongst critics. Craig Gibsone was a major innovator in this direction, presiding over “ecology” workshops promoted and sold with customary exuberance (or spiel) in the annual brochures designed for an affluent international clientele. Grof Transpersonal Training had fallen from favour. Sustainability was the new ploy for income.

The Foundation annual commercial brochures were and are all about the economic factor, whatever the minor thematics varying from A Course in Miracles to neoshamanism. The workshops and courses were widely known to be expensive. This discrepant factor was offset by declarations to the effect that spiritual education was endorsed by the Department of Public Information, indelibly associated with NGO status.

The debt declared in 2001 was given various attempted remedies, such as the mortgage of Foundation properties. The overdraft on Cluny Hill College was stated to be £500,000 (Greenaway, In the Shadow of the New Age, 2003, p. 333; Shepherd, Pointed Observations, 2005, p. 190). In November 2002, that particular debt was declared to be reduced to £305,000, a matter stated in the local press.

Proliferating business drives within the community gave the impression, to superficial scrutiny, of comprising entirely separate enterprises. However, a convergent impulse was evident in this programme. For instance, Duneland Ltd appeared as a separate concern to Eco Village Ltd and the Findhorn Foundation. Close analysts kept track of the integral complexities.

“The leading director and founder of Duneland Ltd is John Talbott, who is also founder and leading director of Eco-Village Ltd” (Greenaway 2003:346). Application for the latter enterprise was accepted by Moray Council in 1997, shortly before Duneland Ltd was announced (ibid:115). Greenaway reports how Talbott (a major celebrity of the Foundation) asserted that The Park and the bordering ecovillage “are one and the same” (ibid:346). This factor of geographical identity tends to support Greenaway’s description of “the Findhorn Foundation conglomerate,” a phrase used to specify the overlapping business activities of this disputed community.

Angus Robertson MP |

The ecovillage team were evidently anxious to enlist the support of Angus Robertson, MP for Moray, who became sympathetic to their cause after Dr. Winifred Ewing retired from her political role in 2003. To quote here from my Letter to the Home Office (2006):

Moray MP Angus Robertson has collaborated with the Findhorn Foundation (abbreviation FF) in their plan to host a new UN training centre in Moray. Robertson has described this as an ‘audacious and innovative proposal.’ The audacity merits investigation. His alliance with the FF has only been in process for about two years, and critics say that he is not duly informed about FF history, much of which has been repressed in the facade presented. Robertson’s enthusiasm has replaced the earlier reserve of Dr. Winifred Ewing, who retired in 2003 after expressing scepticism [of the FF]. She had to wait six months for the FF management to reply to her pressing letter. The incentive for the new UN training centre in [Findhorn] Moray originated within the FF, not within the UN. Robertson has acknowledged the FF as ‘the moving force behind the project.’

The ecovillage celebrities, implied as the prime movers in the UNITAR liaison, are Craig Gibsone, his wife May East, Alex Walker, John Talbott, Michael Shaw, and Jonathan Dawson. They influenced Robertson, who in turn produced a political effect upon Moray Council. The culminating public relations tactic of the Findhorn Foundation, in 2006, involved “lying low” for several months in the face of some criticism. Their dormant publicity vehicle was dramatically reactivated in September, with news of the coup engineered at Geneva via the collaboration of Moray Council.

Practically all of this passed unnoticed to general view, save for the end result. The Scottish Executive were entirely dependent upon what they were subsequently told by the chief mediators in this scheme. UNITAR remained a distant and largely inscrutable Continental mechanism of endorsement, even to Scottish ministers of high standing.

l to r: Craig Gibsone, May East, Jonathan Dawson, Michael Shaw |

The Findhorn Foundation ecovillage project to secure CIFAL status required some length of time to implement, being crucially dependent upon the assisting parties named. All warnings and public complaints were ignored. By gaining UNITAR sanction for the twelfth CIFAL centre on their territory, the Findhorn Foundation moved from the downside economic position to one of prestige advantage for gaining further donations and subsidies. The envisaged economic benefits, coveted by Moray Council (via UN connections), were allowed to obscure the precise nature of what the Findhorn Foundation had been doing for many years in their commercial workshop programme and other activities.

Critical observers subsequently concluded that CIFAL Findhorn operated amiably within the Findhorn Foundation "conglomerate" of commercial enterprises. CIFAL Findhorn Company Ltd did not convince sceptics that a viable ecological role was being demonstrated in the disputed situation. The charges made to subscribers (private and official) attending CIFAL Findhorn Ltd training programmes were substantial, tending very much to underline the business concept involved.

While the ecological content of these programmes seemed applicable, some observers queried the daily rate of charges, varying in 2008 between £100-145. There was a slight reduction for two days at £190-270. Three day attendance was listed at £280-405. Some seminars were restricted to 30 people or less; obviously the scope of financial advantage was then limited. Critics called the phenomenon ecobiz, especially when these subscriber events accompanied the commercial “workshops” in sustainability, chiefly associated with Grof breathwork superstar Craig Gibsone (section 8 below).

However, the partisan view was rather more glowing. Strongly associated with the Findhorn Foundation was GEN (Global Ecovillage Network), becoming a major tool in the promotionalism. Inaugurated in 1995, GEN was funded by Ross Jackson of Denmark, who "became wealthy by designing his own currency trading system." In January 2005, May East promoted the related Ecovillage Designer Education to UNESCO (Paris) and UNITAR (Geneva). This move is reported to have secured UNITAR approval, being the preliminary to negotiations for the CIFAL programme at Findhorn.

Eileen Caddy |

That same year of 2005, the Findhorn Foundation became noted for their declared objective of being “the focal center of a network of light around the planet.” This exotic concept had originated with the predictions of co-founder Eileen Caddy (d.2006), who did not figure in the governing strategies of the community after the early phases associated with the Findhorn Bay caravan park. Her “new age” books continued to be a popular focus for subscribers. However, the economic directive was vested in other entities. GEN became conveniently associated with the "network of light," believed to be of divine origin.

GEN asserted “a new kind of global education” for the twenty-first century. A key word in this project transpired to be sustainability, a monotonous cliche in “workshop” schemes. At the Findhorn ecovillage, Jonathan Dawson became noted for outlining the "economics curriculum" of GEN. There was also said to be an ecological curriculum, a social curriculum, and a spiritual curriculum. Dawson became the President of GEN, also being described in the Findhorn ecovillage promotionalism as “helping to establish the community’s alternative currency (the Eko)." Dawson taught Applied Sustainability and Sustainable Economics up to undergraduate level.

The Findhorn Ecovillage featured an expensive commercial programme under the rubric of Ecovillage Design Education. A four week course in this subject occurred in October- November 2008, being advertised as having the endorsement of UNITAR. The price tag was substantial, stipulating £1595 to £2125 depending upon low or high income of the applicant. A similar range applied to the charges for one week or “module” at £455 to £605. The sliding device for maximal extraction became pervasive within the Findhorn Foundation. The “facilitators” (an American term) of this programme included Jonathan Dawson, May East (the chief executive for CIFAL Findhorn Ltd), and Michael Shaw. Critical observers still wonder at how every subject in this sector becomes a lever for economic contributions.

CIFAL Findhorn Ltd and the ecovillage were ultimately inseparable from the large array of other commercial workshops promoted by the Findhorn Foundation on the same territory. Content in many of these varying “workshops” is controversial. Clients and guests are prone to being misled and miseducated by the pop-mysticism and related themes and practices.

The “transformation” hype remains strong in this sector. The Findhorn Foundation claimed “personal and spiritual transformation” in their activity as a registered educational trust (e.g., the inside back page promotion in Findhorn Foundation Courses and Workshops May-October 2004). Nobody was supposed to argue with this trend, supported by invocations of the UN Dept of Public Information, regularly appearing in the commercial brochures of the Findhorn Foundation. The DPI was not available for relevant consultation even by a prominent senior politician in Scotland.

Jonathan Dawson became a director in CIFAL Findhorn Ltd, but resigned in 2011, prior to the phase of CIFAL Scotland Ltd, during which the personnel contracted to the point of dissolution in 2018. Michael Shaw was also a director in CIFAL Findhorn Ltd from 2009, formerly a colleague of Craig Gibsone in defiant Holotropic Breathwork workshops that did not gain medical approval. Neither Gibsone or Shaw had medical credentials, nevertheless conducting an extreme activity causing some clients to scream uncontrollably or become violent, amongst other manifestations of critical impact.

5. New Age Buddhism

The Findhorn Foundation is attended by associated ventures and independent charities. Arousing criticism was the Shambala Retreat, located at Findhorn in close proximity to the Foundation. In 2005, the Retreat received a substantial loan of £1.36 million from an anonymous donor “connected to the Findhorn Foundation.” The venture was thus able to acquire a large property in the area. There was some speculation about the loan or donation being influenced by the fact that leading directors of the new retreat had long-term status within the Foundation. Craig Gibsone was prominent in the Shambala administration.

The Shambala Retreat was described as an interfaith centre for healing. A therapy message was detected, despite the claim of a Buddhist orientation. A contradictory item, emanating from that new venture, appeared in Rainbow Bridge, the internal magazine of the Foundation. The statement here appeared: “Much of Tibetan Buddhism is outdated and not in tune with the energies of the New Age.” See Update November 2005 to my Letter of Complaint to David Lorimer. Some commentators have accordingly described the Shambala Retreat venture in terms of “new age Buddhism.”

Three years later, in September 2008, the Shambala Retreat for Healing and Universal Compassion gained publicity via the worldwide Maitreya Project Relic Tour. An article in the local press received criticism (“Buddha relics tour offers rare opportunity,” Forres Gazette, Sept. 17, 2008, p. 3). Author John P. Greenaway made clear his objections to that article in a letter to Moray Councillor John Hogg dated 30/09/08. Greenaway here complains that the style of reporting is too reminiscent of Findhorn Foundation marketing extravagances, as in the Gazette reference to “representatives from all the major religions and Buddhist groups will also attend.”

The critic was similarly suspicious of subsequent photographs appearing in the same local newspaper, one of these showing Angus Robertson MP and three Moray Councillors who were present at the unveiling of the Buddhist artefacts. Moray Council is not noted for a prior interest in Buddhism. A political (and economic) intention was suggested. The Parliamentarian and councillors were ignorant of Buddhist complexities, as the critic showed.

l to r: Dalai Lama, Chogyam Trungpa |

Greenaway has some knowledge of Buddhism, more especially the Tibetan variety. His comments are of interest. The press report stated that many Buddhist masters had donated relics for the project under discussion, including the Dalai Lama. John Greenaway here objects:

This seems rather cleverly worded to suggest that the Dalai Lama is supporting this Findhorn Foundation related Shambala project. In fact, the Dalai Lama and the Karmapa, as respective heads of leading lineages who originally supported the Shambala project, both withdrew their support some two years ago.

The Director of Shambala, namely Thomas Warrior, was a close affiliate of the Findhorn Foundation. The press reported him as saying: “We are very excited to host the world-famous Heart Shrine Relic Tour at Shambala for the first time in Scotland.... a very unique event in this day and age.” Greenaway sceptically comments:

This is the Findhorn Foundation hype machine at work! Buddhism does not express itself like this. Show business does! When living in Aberdeen, 2003 to 2007, I attended weekly meditation meetings at a Buddhist venue. They [the participants at that venue] were invited to visit an earlier showing at the Findhorn Foundation of these relics. They declined, on the grounds that this kind of Buddhism is showy, materialistic, and superstitious.

The critic had another grievance which he expressed quite incisively in the letter to hand:

Thomas Warrior, Director of Shambala, at inception cited Chogyam Trungpa as inspiration. This notorious lama, who died in the late 1980s, was a compulsive sex addict (though his followers believe he was taking his devotees’ karma on himself) and long term drug abuser - hash, cocaine, and LSD. When he died (of cyrrhosis of the liver caused by alcoholism), the American who replaced him as head of Trungpa's group was a promiscuous bisexual who already had AIDS. Trungpa had given him a magical mantra, so he believed, which meant he would not pass on the infection to further partners. So he (the successor) continued his sexual pluralism, and of course duly passed on AIDS to several partners (I know Thomas Warrior is not like this at all; my point is, he is naive and only quoted the dead Trungpa after the living heads of Tibetan schools withdrew their support).

A further topic of complaint was broached in the Greenaway epistle on these religious matters:

Thomas Warrior is on record as stating that Tibetan Buddhism is now out of date, as it has been replaced by the New Age. Yet relic tours are distinctly Tibetan Buddhist, and a large majority of Buddhists, including many Tibetans, find them embarassing and feel they should be dispensed with.

6. Trees For Life

A rather different form of activity is also associated with the Findhorn Foundation, namely Trees For Life. Founded in 1981 by Alan Watson, this project was initially part of the Foundation, becoming an independent charity in 1993. The speciality was here tree planting in Glen Affric, the geographical focus in 1991. Critic John Greenaway was appreciative of this activity, observing that an office for the charity was retained at the Foundation property known as The Park. However, Trees For Life “is technically independent of the Foundation conglomerate” (In the Shadow of the New Age, 2003, p. 36).

Trees For Life expanded by purchasing the Dundreggen Estate at Glenmoriston in the Highlands. This acquisition of 10,000 acres involved £1.65 million and also required two years of negotiation. The project entailed the planting of 500,000 native trees to connect (or rather reconnect) the forests between Glenmoriston and Glen Affric. In 2005, Trees For Life gained as a patron the Scottish journalist and broadcaster Muriel Gray, who planted the half-millionth tree that year in Glen Affric.

Glen Affric |

If projects such as Trees For Life were all that comprised the Findhorn Foundation, there would be no opposition from critics like the present writer. I might instead have joined the Foundation when I moved to Scotland many years ago.

As a matter of record here, I did not find much ecological pursuit in evidence at either Findhorn village or Forres, and I lived for a time in both of those places. I did notice that a solitary wind turbine (installed during the late 1980s) functioned at The Park (Findhorn). However, this landmark was not enough to cause any conversion on my part to a very disconcerting milieu dominated by commercial “workshops” and alternative therapy.

Other factors were even more offputting, such as the treatment of dissidents and attendant evasionism posing a total contradiction to any genuine democratic spirit. The new and strongly promoted "eco-houses" were no answer to deeply entrenched problems.

I could never understand why so many visitors to the Foundation preferred to pay exorbitant prices for entrepreneurial new age “workshops” instead of sampling the joys of Glen Affric and other Highland zones that were available for free. All one had to do was bike or motor out to those beauty spots and wild places. Of course, the really hardy types just walk everywhere, but I was getting too old for that.

According to close reports, the Foundation staff were not generally athletic types. They were not in the habit of walking the glens or climbing. The Foundation literature left me unmoved, indeed nauseated. The Eileen Caddy genre of “God spoke to Me” made no difference to my general scepticism, especially as I knew in detail to what extent that co-founder had permitted discrepancies in the annual programme.

Muriel Gray |

One of my initial inspirations of the 1990s was Muriel Gray’s book The First Fifty (1991). That title refers to the mountains known as Munros which are scattered throughout the Highlands. I took to a backpack, waterproof clothing, and solid walking boots. I took my first fifty in two years, and then just kept going, while developing a habit of returning to my favourite locations.

Scotland forever, but an end to predatory “workshops” and evasive managerialism.

7. Dissident Kate Thomas

When I first journeyed to the far north in 1989, I was already a sceptic of the Findhorn Foundation. Their promotionalism repelled me. However, I agreed to suspend judgment because my mother became an associate member of this organisation. She argued that there could be potential for something much better. My suspended judgment turned to deep scepticism as the new drama unfolded.

My mother (Jean Shepherd, alias Kate Thomas) discovered that Grof Transpersonal Training Inc. was being ardently promoted by the Foundation Director Craig Gibsone, who opted to become a practitioner of the disruptive Grof practice called Holotropic Breathwork (hyperventilation). She found that complaints were not tolerated. Objections to managerial policy were regarded as an aberration to be rejected without further hearing.

Another major influence within the Foundation was Alex Walker, managing director of the trading arm New Findhorn Directions. Walker tended to gain the in-house reputation of an adept in “spiritual business,” a phrase also evocative of Francois Duquesne, whose leadership in the early 1980s had “strongly supported expansion beyond the Educational Foundation of the Trust Deed into a spiritually based community, embracing business activity” (Carol Riddell, The Findhorn Community, 1991, pp. 88-9). In the 1990s, Duquesne was one of the Foundation Trustees, who were all found to be evasive and non-communicative about valid complaints addressed to them.

During the early Grof phase, Alex Walker was insisting that “at present the community is in a very healthy state, economically, socially and spiritually” (ibid:223). That very questionable contention did not gain anything from Walker’s denial in the local press that Kate Thomas had ever been a member of the Foundation. Coming from a Trustee of the “spiritual business” community, this inaccurate denial of 1992 was not a good sign for aggregate memory performance of the staff, who continually demonstrated a habit of forgetting or ignoring important details. The obscured membership was reported in a dissident book relaying many facts unwelcome to the Foundation elite (Castro, Hypocrisy and Dissent within the Findhorn Foundation, 1996, p. 15). Thirteen years later, the Foundation management denied that membership in correspondence with a solicitor, confirming the laxity of Foundation officework. That membership was the only reason I agreed to suspend judgment at the time (in 1989). Today, strong critique is essential in the face of deception.

Kate Thomas at Findhorn, 1988 |

Kate Thomas (1928-2017) became the major dissident at the Findhorn Foundation, in the days when Stanislav Grof was regarded as a saviour of alternative therapy. Grof was confused with spiritual achievement. Ecology was just a mute handmaid of the commercial programme. The acute hostilities and distortions achieved by “Education” manager Eric Franciscus were almost unbelievable. To suspend judgment any further (on my part) would have been an act of sheer folly.

I composed an analytical paper on the Findhorn Foundation, appearing in a book (published in 1995) that was too long for the therapy victims to read. They were totally indoctrinated with clichés and entrepreneurial “techniques,” of a very commercial type selling for hundreds of pounds at a time. Grof workshops sold for over £400. Numerous other bizarre inventions were not far behind. The new age was worse than the old age, and based on the same predatory principles of capitalism. However, the vaunted “education” (extolled by Franciscus) was far inferior to anything found in universities.

The drama expanded to include medical doctors, Edinburgh University Pathology Department, the Scottish Charities Office, leading journalists, the local watchdog Sir Michael Joughin, plus others far afield. Many events were recorded by Stephen Castro in an annotated work vilified by the Foundation staff as unfit to read, because they and their policies were the subject of criticism. The disillusioned Castro had also been an associate member. He eventually became a computer technician and an accountant (an employee of the Inland Revenue).

A number of investigators were slow to catch up with these details. The mood is one of amazement that such things could happen under the auspices of a registered charity, gaining NGO status in 1997. The precarious context, in which the Foundation became an NGO, was a precursor to the anomalous situation in which the same organisation gained CIFAL status a decade later (section 2 above).

In more general terms, the partisan tale of how Eileen and Peter Caddy created the “magic of Findhorn” in the 1960s, followed by an ideal “intentional community” fully equipped for UN honours, is one arousing disagreement elsewhere. Too much hagiography and propaganda is discernible. The Hon. Tom Sackville (Chairman of FAIR) stated, in a letter to Kate Thomas (dated 01/10/2007), that the Findhorn Foundation “should not be classed as an NGO.” Some tactics of the organisation at issue have been compared to the tendencies of cults, which are now quite closely defined.

Sackville was responding to the Letter to UNESCO composed by Thomas, dated 01/09/2007. That document afterwards became available on the internet, being a concise statement of the treatment meted out to the author by the Foundation staff and Trustees. She addressed that communication to UNESCO because attempts to contact UNITAR (and the DPI) had proved futile. She reasoned that the good reputation of UNESCO would ensure her letter receiving a due response on behalf of the United Nations. UNESCO is the abbreviation for United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation. This body has a somewhat higher repute than the Dept of Public Information (DPI), associated with formal investiture of the Foundation with NGO status.

Thomas was disappointed when UNESCO failed to reply. Not even the briefest acknowledgment was forthcoming from the official to whom her lengthy letter was addressed. In contrast, the Prince of Wales sent an exquisitely courteous response to the copy despatched to him.

Subsequently, Kate Thomas sent a much shorter epistle to the Director of the Findhorn Foundation, namely Bettina Jespersen. This letter, dated 23/11/2007, is here reproduced in full:

Dear Bettina Jespersen,

I am enclosing a copy of the letter sent to Koichiro Matsuura, the Director General of UNESCO, on 1/9/2007, regarding the Findhorn Foundation and their treatment of myself and colleagues as described on the recently presented website www.citizeninitiative.com – a letter to which I have still received no reply. I would be grateful if you would now personally look into this matter and inform me why for so many years I have been stigmatised and excluded, and why others, namely Gemma Whibley, Jill Rathbone, and Dr. Sylvia Darke, were banned from the Foundation for supporting me. I have never been given a reason for this, and the lack of response from Koichiro Matsuura perhaps indicates that he was not given one either.

It is one thing to have this treatment administered by a little-known New Age organisation, but quite another for it to be applied by a part of the CIFAL network backed by UNITAR, which is why I am making this request. Similarly, my many pleas over the years for an official hearing have been likewise ignored.

In anticipation of your response,

Sincerely,

Jean Shepherd

P.S. You may know of me as Kate Thomas, the pseudonym used for my published books.

cc. May East, CIFAL Findhorn Project Director.

There was no reply to this letter from either Jespersen or May East (the wife of Craig Gibsone). May East held the key executive position in CIFAL Findhorn Ltd, related to the Foundation campus. Thomas had no prior contact with Jespersen, who was a recent Foundation Director. She had formerly encountered East, without any friction occurring.

Kate Thomas, Findhorn 1988 |

Subsequently, Thomas agreed to contact her local Member of Parliament (as Tom Sackville and others had advised her). In August 2008, she obtained an interview with Robert Walter, MP for Dorset, who proved very sympathetic to her case. Walter expressed surprise at the extent of the evasive treatment about which Thomas complained in relation to the Findhorn Foundation. He was of the firm opinion that UNESCO needed to be recontacted, and that the Foundation required a separate reminder of their negligence.

Robert Walter MP accordingly sent communications to both UNESCO and Bettina Jespersen. This was in late August. There did ensue a brief reply from UNESCO. The relevant email, dated 02/09/2008, came from secretary Kate Overton, on behalf of the Office of the Director General at UNESCO. This communication read as follows:

Effectively, the Findhorn Foundation is not affiliated with UNESCO’s NGO and IGO system. I regret therefore, that we will not be able to respond to Mrs Shepherd’s enquiry.

Many thanks for your assistance.

Best wishes,

Kate Overton

This response from UNESCO evoked much word for word and contextual analysis. The prestigious body was obviously not prepared to say anything more on the subject. UNESCO were effectively disowning any link with the Findhorn Foundation. The abbreviated nature of the response aroused some comment in the circle of acquaintances of Kate Thomas. This format was considered to be a drawback of current bureaucratic agendas. However, a logical deduction was made that any further claim of the Foundation to have UNESCO auspices, however indirectly, would not be supportable to informed parties. The response of UNESCO annulled various associations in that direction which the Findhorn Foundation had made over the years in promotional literature.