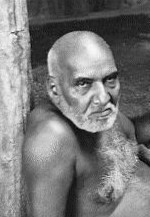

l to r: Shirdi Sai Baba, Upasani Maharaj |

l to r: Shirdi Sai Baba, Upasani Maharaj |

The conflatory phrase "Sai Baba movement" refers to a complex phenomenon which has been given different interpretations. That strongly disputed phrase encompasses the entities known as Shirdi Sai Baba, Upasani (Upasni) Maharaj and Godavari Mataji, Meher Baba, and Sathya Sai Baba. The treatment below analyses components of the presumed convergence, with the primary accent on Shirdi Sai Baba.

CONTENTS KEY

1. Introduction

7. Religious Syncretism in Maharashtra

10. Meher Baba

11. The Sai Baba Movement at Issue

12. Sectarian Globalisation and Devotional Memory

Update: Tulasi Srinivas and the Politics of Religion

The phrase "Sai Baba movement" was innovated by followers of Sathya Sai Baba (d.2011), being employed in some academic texts. The State University of New York Press stated on the cover of a well known book: "A vast and diversified religious movement originating from Sai Baba of Shirdi, is often referred to as 'the Sai Baba movement.' Through the chronological presentation of Sai Baba's life, light is shed on the various ways in which the important guru figures in this movement came to be linked to the saint of Shirdi."

This influential SUNY promotion related to the contents of Antonio Rigopoulos, The Life and Teachings of Sai Baba of Shirdi (SUNY Press, 1993), a work including some deference to Sathya Sai Baba. The same book also referred to Upasani Maharaj and Meher Baba.

The designation of "Sai Baba movement" represents an academic theory. In practice, three of the devotional movements involved do not favour this usage, not regarding Sathya Sai Baba as a priority. Moreover, the Sathya Sai movement frequently abbreviates the theory to a proposed connection between Shirdi Sai Baba (d.1918) and Sathya Sai Baba (d.2011). The extensions in relation to Upasani Maharaj (d.1941) and Meher Baba (d.1969) are too frequently omitted. An exception to this convenience was my own non-sectarian book Investigating the Sai Baba Movement (2005).

I have found that general readers are often confused by the academic theory. In 2012, some American followers of Meher Baba even tended to imagine that I had invented the phraseology involved. In the face of widespread non-comprehension, it is relevant to take account of the various presentations, and to analyse accordingly. Some of the issues are controversial.

Devotees of Shirdi Sai Baba have been known to use the counter phrase Shirdi Sai Baba Movement, evidently to distinguish themselves from associations with Sathya Sai Baba. Whereas devotees of Sathya Sai Baba have employed the phrase Sathya Sai Baba Movement.

The career of Shirdi Sai Baba is distinctive. Complexities relating to his religious background enliven the portrayal. I am not myself a devotee or sectarian, approaching him from another angle, commencing with a book published over thirty years ago. (1)

Sai Baba of Shirdi is frequently known as Shirdi Sai Baba, the purpose here being to distinguish him from his controversial namesake, Sathya Sai Baba of Puttaparthi. In 1943, the latter claimed to be the reincarnation of the Shirdi saint. That sensational claim facilitated the rise to fame of the young Sathyanarayana Raju, alias Sathya Sai Baba (officially born in 1926). Born in or near the village of Puttaparthi, in Andhra Pradesh, the putative successor appropriated the name of the Shirdi saint, an event which has not been viewed with favour by devotees of Shirdi Sai. The Andhra celebrity subsequently claimed and elaborated the prerogative of avatarhood, meaning the role of a divine incarnation.

Most followers of Shirdi Sai have not accepted the reincarnation claim. Yet some books, by devotees of Sathya Sai Baba, interpose lore about the Shirdi saint deriving from the Puttaparthi celebrity. This trend has caused confusions.

Islamic Tombs at Khuldabad |

Two different geographical areas are represented by the two bearers of the name Sai Baba. The original entity lived in Maharashtra, a Marathi-speaking state. Whereas the proclaimed reincarnation emerged in Telegu-speaking Andhra, located further south.

The favoured language of Shirdi Sai was Urdu, an Islamic tongue widely used by Indian Muslims. In this respect, one requires to emphasise the Muslim occupation of the area formerly known as the Deccan. That term broadly signifies the Deccan Plateau, a vast territory covering Maharashtra, Andhra, and Karnataka. The Muslims invaded the Deccan in the thirteenth century (after centuries of complex Sufi developments in Iran and Central Asia). Various cities of the Deccan are strongly associated with the Islamic occupation, e.g., Hyderabad in Andhra, and Aurangabad in Maharashtra.

A little to the north of Aurangabad is the medieval town of Khuldabad, strongly linked with the Chishti Sufis. This place became a major Sufi pilgrimage centre in the Deccan. Scholarly discussion of Deccani history has found in the Khuldabad tradition a foil to the idea of militant religious activism, equated with Sufism via the ghazi religious warriors of the Anatolian frontier and the early Safavid state in Iran. (2) The “Warrior Sufi” interpretation arose in relation to Bijapur, a city in the southern Deccan, where a strong Sufi presence is also attested. The “Warrior Sufi” attribution has since been viewed as an exaggeration. (3)

Khuldabad Tombs, including that of Zar Zari Zar Bakhsh |

In the fourteenth century, the Sultan of Delhi transferred his religious and administrative elite south to Daulatabad, located in Maharashtra. For a time, this city functioned as the new Islamic capital in India. The enforced move south, in 1329, included many Sufis of the emerging Chishti Order. A substantial number of these men elected to remain at Daulatabad when Delhi again became the favoured administrative centre of the Sultan. Relations with the monarch had become strained. (4)

Near Daulatabad and Aurangabad, the town known as Khuldabad (Rawza) became a major Sufi pilgrimage site in subsequent centuries, being noted for many domed tombs (dargahs) of Sufis. Khuldabad is rather less than a hundred miles from Shirdi, gaining in some quarters an association with the faqir Sai Baba, who is said to have stayed in a Chishti-related cave during his obscure early years. This association does not prove any Chishti identity of the Shirdi saint. (5)

3. A Liberal Muslim Sufi

Hyderabad, a major Islamic centre, was a home for the Urdu language evolving in response to the Hindu environment. Urdu is described as a form of Hindustani incorporating many Persian and Arabic words. Urdu became the official literary language of Pakistan. Many years prior to that development, Shirdi Sai Baba was a speaker of Deccani Urdu. He adapted to Marathi, a language he also spoke. A controversial matter is that his basic linguistic and cultural affiliations reveal him as a Muslim, and more specifically, as a Sufi of the liberal and unorthodox variety. (6)

Sai Baba of Shirdi emerges in early accounts as a Muslim faqir or ascetic. He wore the typical garb of that category. The date of his birth is unknown (though attributions have been made). His early life is obscure and legendary. Nevertheless, there are certain indicators afforded. An important early report is dated 1911, surfacing only recently. This testimony came from the British policing department based at Calcutta. The report describes Sai Baba as a faqir, adding the words “said to be a Mahomedan” (Satpathy 2019:30).

The early British report refers to Sai Baba as “an old man of about 70 who came to Shirdi some 30 or 35 years ago and put up in the village mosque where he has resided since” (ibid). The assessment of his age is not definitive. Dr. C. B. Satpathy favours the date of 1872 for the arrival of Sai Baba in Shirdi (ibid:34). This dateline converges with former estimates of Narasimhaswami and other sources.

Shirdi, a village in the Ahmednagar district of Maharashtra, was inhabited largely by Hindus. Only about one tenth of the population are estimated to have been Muslims. The Hindu villagers at first regarded Sai Baba as an alien, as a Muslim faqir unsuited for entry into Hindu temples. Sai Baba made his abode in a dilapidated mosque of rural dimensions. One of his early Muslim disciples kept a notebook in Urdu, permitting a strong insight into the Sufi orientation of the Shirdi saint.

The Muslim disciple Abdul Baba was a close servitor of the Shirdi saint for almost thirty years until the latter’s death. Thus, we know that the "Sufism" exposited by Shirdi Sai was apparently in evidence from 1889 until his last years. Abdul would read the Quran in the presence of the saint, at the latter’s request. During these sessions, Sai Baba would make diverse utterances, some of these being recorded in the Notebook. Abdul's Urdu manuscript was not published in any form until 1999. (7) The basic and underlying significances had passed into oblivion.

Dr. Marianne Warren observed:

The manuscript largely pertains to Muslim and Sufi material in Deccani Urdu; there are a number of quotations in Arabic included from the Quran and hadith [traditions of the Prophet].... the fact that the manuscript’s Islamic nature does not fit in with the accepted Hindu interpretation and presentation of Sai Baba may explain why it has remained unpublished. (8)

Moreover, the translated Urdu Notebook “establishes beyond doubt that Sai Baba was totally familiar with both the Islamic and Sufi traditions, and that as a Sufi master he taught this tradition to Abdul." (9) However, Sai Baba did not generally project himself as a Sufi master, remaining allusively neutral to different religious traditions. He was not interested in conversion to a belief system. Instead, he favoured parables that were often difficult to understand.

Shirdi Sai Baba |

The major devotional biography, written in Marathi, likewise confirms the Muslim background. Unfortunately for popular assimilation, this book by Govind R. Dabholkar (alias Hemadpant) gained a very misleading English adaptation that seems to have been more widely read than the original.

The Marathi biography, entitled Shri Sai Satcharita, was composed by an early brahman devotee who repeatedly acknowledged and indicated the Muslim faqir identity of the saint. However, the English adaptation by N. V. Gunaji neglected to include the Muslim context, instead improvising a Vedantic complexion to the subject. (10) For instance, Gunaji ignored the frequent use of Urdu by Shirdi Sai. He omitted sections of the Dabholkar work referring to Muslims, Muslim practices, and Sufi teachings. Gunaji deleted reference to the Islamic ritual of goat slaughter (takkya). In contrast, Dabholkar duly reported that the saint would occasionally permit this ritual so abhorrent to Hindus (without himself participating in the slaughter).

The name (or rather title) of this saint is evocative of Muslim origins (though not definitive as to religious identity). The word Sai appears to be derived from the Arabic sa’ih, a term used to designate itinerant ascetics in the Islamic world. (11) The word Baba is sometimes given a Hindu context, which is only partially correct. Baba is a common Marathi expression meaning “father.” The word was also employed in the medieval Indian Sufi tradition. The Turkish word baba referred to diverse preachers and shaikhs, having an origin in the itinerant babas from Central Asia. (12)

The first festival performed in Sai Baba’s honour was significantly that of the urs, in 1897. The urs is a Muslim festival, and usually commemorates the anniversary of a saint’s death, though in this instance it celebrated a living saint who was being honoured by a Hindu, Gopalrao Gund of Kopergaon, who attributed to Sai the birth of his son. The Muslim background of the saint was so obvious that Gund had to honour him in Islamic terms. (13) [The word urs comes from the Arabic language]

Sai Baba was frequently believed by Hindus to confer the blessing of childbirth. Many instances of this are reported in the hagiology. Social and religious taboos had conspired to make a childless couple seem very undesirable in Hinduism; a strong stigma could result. Women were particularly subject to the accusation of disgracing the family. A male child was highly prized. There were thus compulsive reasons for this preoccupation with progeny, frequently projected onto holy men, who were believed to be an alleviating factor.

The Hindu followers eventually came to substantially outnumber the Muslim devotees. From about 1910, an urban influx of Hindu admirers was in strong evidence at Shirdi. Sai Baba was welcoming and inclusive, not being a doctrinaire exponent of Sufism. He did not preach, instead advocating a religious tolerance extending to Christianity and Zoroastrianism. Sai Baba referred amenably to Hindu gods and avatars, and permitted arati worship at his mosque. Frequently resorting to allusive speech, he tended to be very enigmatic.

4. The Hinduization Process

In the Shri Sai Satcharita, Dabholkar records: "A Hindu or a Muslim, to him [Sai Baba] both were equal" (Indira Kher trans., p. 165). This feature of universalism can easily be overlooked, or modified, by religious preferences.

The theme of "Hinduization" was emphasised by Dr. Marianne Warren, who urged that an overlay occurred in much reporting about Sai Baba, tending to obscure the Sufi dimensions of his profile. One is obliged to probe this factor (without necessarily endorsing all the contentions and suggestions of Warren about Sufism).

The Shirdi saint was believed to possess an intimate knowledge of Sanskrit, the language of Hindu scriptures. This attribution was based upon his explanation of a verse in the Bhagavad Gita, a classic text associated with Vedanta. This explanation was imparted to a Hindu devotee. Subsequent analysis has strongly contested the "Sanskrit" theory, favoured by B. V. Narasimhaswami, who relayed an earlier report. “That interpretation was followed by other writers, and served to strengthen the tendency to portray the saint in a Hinduized manner.” (14)

Sai Baba's explanation of the Gita verse is described by Warren as “totally different” to the version of Shankara and other canonical Hindu commentators. In this view, the relevant dialogue does not in fact prove that Sai Baba knew the Gita or even Sanskrit, his emphasis being Sufistic. The version of Dr. Warren stresses that the saint gave a unique interpretation. He did not need to know the text at all, as the verse was read out to him along with a statement of grammatical meanings. This was done at his own request. “Sai Baba had all the raw material of the verse given to him, so there is no basis to the supposition that he in fact ‘knew’ Sanskrit or even the Bhagavad Gita." (15) There are various complexities attaching to the dialogue.

Sai Baba the faqir |

During his lifetime, the saint was generally regarded as a Muslim faqir, with Sufi associations not in general well understood. His white robe (kafni) and headgear were clearly Muslim. He used the Islamic name for God, and repeated Islamic sacred phrases, not Hindu mantras. He even had a habit of referring to God as the Faqir. However, his liberalism was so pronounced that no distinct religious message could be attributed to him. He was a believer in reincarnation, a subject that is not generally associated with Sufism.

The influx of urban devotees from Bombay, in the last years of Sai Baba, made the Hindus a clear majority in his following. Tendencies to "Hinduization" appeared in the later reports, obtained from devotees who were interviewed by Narasimhaswami in 1936. Eighty persons were then interviewed, although only 51 have a clear religious identity. No less than 43 of those were Hindu, with 26 of that contingent being members of the elite brahman caste. Only four were Muslims. There were also two Parsi Zoroastrians and two Christians. (16)

A revealing factor emerges. Narasimhaswami asked all the devotees he interviewed a rather pointed question. Did they think that Sai Baba taught Vedanta? “In all cases they said he did not.” (17) It can therefore seem anomalous that Narasimhaswami promoted a theme of the Sanskrit expert based on a Vedantic text. In the 1940s, Gunaji was giving an erroneous impression, via his Vedantic interpretations of the Shirdi saint, which cannot be found in the original work by Dabholkar that Gunaji was rendering. According to Professor Narke, a prominent Hindu devotee, the affinity of Sai Baba was not with Vedanta or Yoga, but with Bhakti.

Narasimhaswami had never met Sai Baba. This sannyasin arrived at Shirdi nearly twenty years after the saint’s demise. He was not familiar with either Marathi or Urdu. (18) His books on the subject became very influential amongst Hindus. He did refer to Sai Baba as a Muslim, and one whose teachings were indistinguishable from Sufism. He nevertheless admitted to knowing little about Sufism, himself clearly preferring the bhakti (devotion) approach of Hinduism.

Narasimhaswami could reason that Sai Baba was apparently a Muslim because he lived in a mosque. However, the commentator was very partial to a report (of Mhalsapati) which claimed that the saint was a brahman by birth. The version of Narasimhaswami can convey the impression of regarding the subject as a Hindu, not as a Muslim. Sai Baba himself showed no concern with religious identity.

The influential testimonies provided by Narasimhaswami are varied in complexion. That enthusiastic promoter of the “Shirdi revival” produced a work entitled Devotees’ Experiences of Sri Sai Baba (1940). This has a substantial documentary value, but also includes hagiology, which has been differently assessed. An academic commentator described the same book in terms of:

a detailed presentation of alleged miraculous phenomena.... the intent of the work is clearly hagiographic, aiming at the expansion of Sai Baba’s popularity among the public at large. (19)

Narasimhaswami later produced in English a four volume biography of the saint, which likewise has a documentary value. However, that work exhibits a strongly Hinduizing gloss. Two of those volumes draw from reports of devotees the author had interviewed. Narasimhaswami says: "Externally the mass of Hindus regarded him as a Muslim but worshipped him as a Hindu god." The same commentator also stated, with honesty, that the ideas and teachings with which the saint was saturated "up to the last were in no way distinguishable from Sufism." (20)

In his last years, Sai Baba freely allowed his Hindu devotees to perform puja (worship) before him at the mosque. This concession annoyed Muslims, creating initial problems. (21) Despite the liberal attitude of the saint to Hindu religious tendencies, he continued to make constant reference to Allah and maintained the simple kafni (robe) of the Muslim faqir.

Shirdi Sai was ruggedly ascetic to the end, daily begging his food from local houses. He redistributed money (or dakshina) that he requested. He did not keep or hoard funds.

Sai Baba on his daily begging round in Shirdi |

Discrepancies in reporting apply to such episodes as the alleged wrestling match of the saint, in Shirdi, with Mohiuddin Tambuli, a Muslim. The event is undated. According to Dabholkar (and Gunaji), Sai Baba lost this contest, thereafter changing his apparel to the kafni of faqirs. In contrast, the Hindu informant Ramgiri Bua emphasised that Sai Baba did not wrestle, instead having a disagreement with the son-in-law of Tambuli, as a consequence of which the faqir retreated to the nearby wilderness. This obscure episode has been tentatively dated to the 1880s. (22)

The popular theme of Sai Baba as a miracleworker is misleading. He did not perform “miracle” stunts like some Hindu holy men. This faqir was merely in the habit of giving sacred ash (udi) from his dhuni fire, as a token of blessing. The ash became credited with healing properties. Devotees like Dabholkar did strongly credit him with miracles, generally of the minor variety, a frequent preoccupation being the birth of a child. Sai Baba himself is reported to have expressed annoyance at the mundane desires entertained by visitors.

In temperament, Shirdi Sai Baba was complex. Sometimes irascible with lax devotees, he could also be very patient, and liked to joke. His strong tendency to allusive speech, in his later years, was perhaps prompted by the gulf existing between different religions. There was another contrast between the renunciate lifestyle and the householder career. Most of the devotees were householders, meaning those in the married state. Their domestic preoccupations were far removed from the ascetic milieu which Sai Baba represented.

A revealing situation emerged in relation to devotees who proved aberrant: "A few of them even played various tricks, including sentimentalizing trivial issues to extract money from Sai Baba on some pretext or other. Some became boisterous in their demands and quarrelled in front of Sai Baba. The compassionate Sai Baba tolerated this nuisance for long but, at times, reproved them for not being ethical in their conduct. In spite of many admonitions, there was no qualitative improvement in the situation. Sai Baba expressed his exasperation in Marathi language" (Satpathy 2019:115).

In 1915, this situation contributed to the Dakshina Bhiksha Sansthan being created at his request. For long obscured, this development has recently gained due focus. The attempt to control perverse inclinations of petitioners aroused resistance. The problems included "manipulation and extraction of money and food items from Sai Baba on various pretexts" (ibid:120). See further Sai Baba Versus Impertinence.

At his death, there was a disagreement amongst the followers of Sai Baba about burial procedures. The Muslim minority are reported to have included the category of theologians known as maulvis and maulanas. An air of dignity would thus have attended the argument. The Muslims wanted Sai Baba to be buried in a Sufi tomb or dargah of the type well known in the Deccan. In contrast, the Hindu majority wanted the saint to be buried in the courtyard of a large house (wada), recently constructed by the wealthy Hindu devotee Gopalrao Buti.

The Hindus were victorious, the Muslim proposal being offset by the heavy expense involved. However, the Hindus deferred to Muslim sensitivities, initially permitting the new tomb interior to resemble a dargah, and making Abdul Baba the custodian of the shrine. These details indicate that the Muslim identity of the saint was still clearly recognised by the Hindu majority.

After a few years, however, Abdul was denied his role as tomb custodian in 1922. A prominent Hindu devotee, Hari Sitaram Dixit, overruled the authority of Abdul by setting up a Public Trust through the Ahmednagar District court, with the intention of administering the tomb. Abdul was persuaded by sympathisers to challenge the court ruling. He filed a counter-suit declaring that he was the legal heir to Sai Baba, and that the Public Trust was illegal. Abdul lost his case, being obliged to leave the room reserved for him at the shrine. The severe restrictions were relaxed at a later date. However, the Muslim claim to dominance was permanently eliminated.

The new official Sansthan (Trust) was exclusively composed of Hindu members. The tomb at Butiwada became known as the samadhi mandir. During the 1950s, a marble statue of Sai Baba was installed on a silver throne; above the statue was placed a sign identifying Sai Baba with the Hindu avatar Rama. Acccording to Warren, this innovation caused offence to Muslims; faqirs are reported to have stopped visiting the tomb. (23) In contrast, the substantial Hindu support increased over the years. Shirdi became a famous and expanding pilgrimage site. The samadhi mandir is reported to gain a large number of annual visitors from Mumbai and other cities.

Writers who followed in the wake of Gunaji and Narasimhaswami, were strongly influenced by the "Hinduization" tendency. A Parsi writer composed a chapter entitled “What the Master Taught.” There is not a single reference to Sufism, but instead many to Hindu bhakti, and also one or two that can be interpreted in terms of a simplified Vedanta. Furthermore, another chapter includes the statement:

The saint of Shirdi baffled his admirers! No one knew whether he was a Hindu or a Muslim. He dressed like a Muslim and bore the caste marks of a Hindu! (24)

The equivocal theme of “Hindu or Muslim” had replaced the earlier awareness that Sai Baba was a Muslim faqir. The reference to caste marks is superficial, arising from hagiological tendencies.

5. Some Aspects of Teaching

The teaching of Sai Baba did not occur in the generalising terms associated with gurus and pirs. He was not a preacher, and did not give lectures. The original Hindu devotees, like Dabholkar, testify that he was constantly uttering Islamic sacred phrases such as “Allah Malik” (God is the Owner/Ruler). Vedanta is not here evident, but rather a version of the Sufi theme tauhid (unity, oneness of God). However, no doctrine was transmitted. There were instead many parables, enigmatic statements, and ethical reflections. In various ways, the Shirdi faqir emphasised a religious liberalism.

During his last years, Sai Baba permitted his brahman devotee Bapusaheb Jog to read aloud and expound Hindu scriptures at the Sathewada (a building in Shirdi). Jog would relay the Jnaneshvari and the Eknathi Bhagavat, texts associated with the Maharashtrian bhakti tradition. The faqir would tell visiting Hindu devotees to attend the daily sessions held by Jog, who was proficient in Sanskrit. Such events convey the liberal attitude of Sai Baba.

The Urdu Notebook of Abdul relays that Sai Baba strongly criticised false Sufis, and also corrupt orthodox (Muslim) divines who accepted bribes. The Notebook "includes conciliatory verbal gestures to Hindu themes, testifying to the fact that Sai Baba was not insular." (25)

Biases against Muslims are unfortunately prevalent today in both America and India. This factor has to some extent hindered due assimilation of relevant facts and textual references in the case of Sai Baba. Researchers are not obliged to believe that this saint was a Hindu because of political preferences. As a very rare category of non-dogmatic faqir, he remains largely unknown a century after his death. See Shirdi Sai Baba Issues.

6. The Pathri Legend

The British writer Arthur Osborne became well known for his interpretation of Ramana Maharshi. He also wrote The Incredible Sai Baba (1957). This book formed an introduction to the subject for most Westerners prior to the 1980s. Osborne made a sympathetic attempt to decipher the Shirdi saint, grasping that he was not typical of the Hindu guru category. However, his commentary does not refer to a Sufi context. Osborne reports that Sai Baba was regarded as a Muslim faqir, but does not supply any due contextual description. The Western writer was strongly influenced by works of Narasimhaswami. Osborne states of Sai Baba:

It is fairly certain that he was born of a middle class Brahmin family in a small town in Hyderabad State. Possibly his parents died when he was young, because at a very early age he left home to follow a Muslim fakir. (26)

Some analysts are sceptical of this version. Narasimhaswami favoured a report gleaned from Mhalsapati, a Hindu priest who became one of the earliest devotees. According to this source, Sai Baba revealed in his later years that his parents were brahmans of Pathri. If there is any truth in that now popular legend, then Hindu parentage was quickly superseded by a Muslim ascetic lifestyle. The Pathri legend has become influential. However, less well known details can afford a different complexion.

Pathri is a small town in Maharashtra, in the Aurangabad region. Warren reported that sixty per cent of the Pathri population is Muslim, a fact reflecting the strong Islamic concentration in this zone. Pathri was a known centre of the Qadiri Sufis, and features Sufi tombs dating back to the medieval era. The most salient tomb (dargah) is that of Sayyad Sadat (Aminuddin Shah), whose urs festival (death anniversary) has been popular amongst both Hindus and Muslims. (27)

Sai Baba is noted for giving contradictory replies to questions concerning his parentage and origins.

7. Religious Syncretism in Maharashtra

Strong tendencies to Hinduize the subject influenced writers like Arthur Osborne into making the Shirdi saint a subject of equivocal affiliation. According to Osborne, Sai Baba “did not fully conform to either” religion, meaning Islam and Hinduism. To some extent this is true enough. Nevertheless, details have to be carefully fathomed. Osborne states that Sai Baba was a vegetarian. (28) The vegetarian theory has since been exposed as a myth, one inadvertently siding with the Gunaji excision of Dabholkar's reference to the Islamic ritual involving goat slaughter. Sai Baba did eat meat in the company of Muslims. In contrast, on his daily begging round (at Hindu houses) he was restricted to vegetarian food. The faqir was thus a vegetarian to Hindus, but not to Muslims.

The most convincing explanation, for the Shirdi phenomenon, is that Sai Baba's assimilating approach to Hinduism represented a continuation of syncretistic trends operative between Muslim Sufis and Hindus. Indeed, Sai Baba's enlightened (if at times eccentric) form of syncretism can appeal equally to the sociological and religious modes of analysis. The Shirdi saint represented a Muslim minority amongst a Maharashtrian Hindu majority. Avoidance of Sufi significances has the effect of reducing the scale of his achievement.

Sai Baba with Hindu devotees |

In his interactions with Hindus, Sai Baba made diverse references to Hindu gods. That gesture can be interpreted in terms of a liberal Sufi tendency. His speech was frequently so allusive that even the word brahman has been tagged as symbolic. (29) The story of a Hindu guru, favoured in some sources for the early life of the saint, has been discredited by critical scholarship. (30) The Hindu scholar V. B. Kher (associated with the Shirdi Sansthan) arrived at a memorable conclusion. “The fact that Sai Baba's guru was a Sufi is not a matter of surprise." (31)

The first major account of Sai Baba achieved an elite reputation amongst Hindu devotees. Hemadpant was the name bestowed by the saint upon his brahman devotee Govind Raghunath Dabholkar. The contact of Dabholkar with Sai Baba commenced in 1910, subsequently resulting in the devotional biography known as Sri Sai Satcharita. Written in Marathi verse, this work was published in 1929. Dabholkar was here following a long Hindu tradition of writing saintly biographies in verse format.

Dabholkar was at times concerned to describe miracles of the saint. Nevertheless, the factual dimension is strong. Legendary details and actual events have been discerned to overlap, requiring careful analysis. Another realistic assessment concerning the work of Dabholkar is: “When he did not understand the enigmatic mystic, he would rationalize sayings and events in conformity with his own religious background.” (32)

Dabholkar’s poetic biography assimilated a devotional tendency to identify Sai Baba with the god Dattatreya, often depicted as an ascetic or yogi. Various Hindu gurus gained repute in the nineteenth century as incarnations of the ascetic deity Dattatreya. A well known instance of Dattatreya association is Swami Samarth of Akalkot (d.1878). A subsequent “Dattatreya guru” was Narayan Maharaj of Kedgaon (1885-1945); this ascetic favoured an opulent lifestyle in his later years, while acting as a patron of Dattatreya worship at his ashram. (33)

At the beginning of each chapter, Dabholkar extols Sai Baba as Shri Sainath, in the context of an obeisance to tutelary deities like Ganesha and Saraswati. The Shirdi faqir is here totally compatible with Hinduism. "O Self-illumined Sainath, to us you are truly, Ganadheesh and Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh." (34)

In the opening chapter, Dabholkar extols Hindu gods, also referring to the bhakti saints of Maharashtra such as Eknath and Tukaram. The Eknathi Bhagavat has been discerned as a strong influence in his direction. Yet Dabholkar "fails to mention any Muslim saints or famous Sufis, although there were many whose names were quite famous in Maharashtra.” (35) According to Dr. Warren, the overall impression conveyed by the work under discussion is that Dabholkar “personally regarded Sai Baba as a Muslim, although he was limited in fully understanding Sai Baba's Muslim-Sufi identity due to his own ignorance of Islam and Sufism in Maharashtra." (36)

Dabholkar includes the emphasis, closely associated with Sai Baba, that “Ram and Rahim are one and the same.” Ram here means the Hindu avatar Rama, while Rahim is an Islamic sacred name. The same writer reports that Sai Baba associated with all castes and outcastes, ignoring the conventional caste distinctions. Such achievement needed stressing to the caste bigotries prevailing in Maharashtra and elsewhere in India. To numerous (but not all) high caste Hindus, the Muslim faqir was an outcaste, considered unfit to enter temples.

Dabholkar (12:151ff) provides an instance of the formidable bias encountered. A Ram bhakta (devotee of Rama) had strong reservations about visiting Shirdi. This man was a brahman, and said: "I cannot bring myself to make obeisance at the feet of a Muslim." His friend, a mamlatdar (revenue official), urged that nobody would request him to perform any obeisance to Sai Baba. Thus reassured, the Rama devotee agreed to visit Shirdi. When he arrived at the mosque, he made a prostration to the saint of his own accord. His accompanying friend was amazed, asking the reason for this concession. "How did you prostrate before a Muslim?" The brahman related that he had seen Rama in the person of Sai Baba; he had not been aware of any Muslim presence. Now the visitor reasoned: "How can he [Sai Baba] be a Muslim? No, indeed! He is a yogi, an Incarnation of God!"

Dabholkar comments that the caste background of saints was not important. "The great saint Chokhamela was a mahar [untouchable] by caste; Rohidas was a cobbler; Sajan was a butcher, who killed animals for a livelihood. But who ever thinks of the caste of these saints?" (37)

Dabholkar faithfully reported another significant episode. A Hindu devotee (Dr. Pandit) was allowed by the saint, on one occasion, to apply sandal paste to his (Sai Baba’s) forehead, thus reproducing the tripundra emblem of the Shaiva tradition (i.e., of Shiva). When questioned afterwards as to why he permitted this form of worship, Sai Baba explained that, although he (Sai) was of the Muslim caste (mi jatica Musulman), Dr. Pandit thought of him as a guru and was here performing ritual worship to the guru (guru-puja). The saint then revealingly added: "He (Dr. Pandit) did not even entertain the thought that he was a pure brahman and that I was an unclean yavana (Muslim)." (38)

The overall liberalism of Sai Baba, in a divided religious milieu, is remarkable to an extent as yet only partially comprehended.

8. Insularism and Unorthodoxy

The reported statement of Sai Baba that “I am of the Muslim caste” is significant. In passing from Dabholkar to the adaptation of Gunaji, we encounter omission in this respect. Gunaji evidently resisted any prospect of the saint having been a Muslim.

In a well known passage preserved from Dabholkar, Gunaji poses the question: If Sai Baba was a Muslim, how could he keep a dhuni fire burning in his mosque, and how could he keep a sacred tulsi plant in the yard outside, and how could he permit Hindu music, and how could he have pierced ears, and how could he have donated money to repair Hindu temples?

The tolerance of Sai Baba in relation to Hindu ceremonial adjuncts was notable. This feature of tolerance does not invalidate his own (excised) statement that he was a Muslim. (39) The insular thinking can be contradicted; Sai Baba was not an orthodox Muslim, but a very distinctive and unorthodox Sufi faqir.

The sacred fire or dhuni, associated with Hindu holy men, was also favoured by Muslim faqirs. (40) The issue of pierced ears is not definitive. Many Hindus gained pierced ears at birth. Hindu biographers have urged that the Shirdi saint had pierced ears. Against this must be set an assertion of the prominent Hindu devotee Das Ganu, in a well known poem, that Sai Baba can be called a Muslim because of such characteristics as his ears not being pierced. Das Ganu added his own conclusion that the saint was a Hindu, adducing the dhuni fire as support. Dabholkar is also contradictory, favouring pierced ears while affirming that Sai Baba was circumcised. (41)

As to the repair of Hindu temples, in his last years Sai Baba gave away large amounts of money, daily gifted to him as dakshina or alms. His mosque was repaired by Hindu devotees; a reciprocal gesture was surely appropriate. He did not actually want any renovation of the ramshackle mosque. An affluent devotee pointedly dumped cartloads of stone outside the building. The saint responded by telling him to give the stone to temples. Sai Baba eventually agreed to the renovation but continually interfered with the project, to the extent that workmen could only be on the site during nocturnal hours. Sai Baba insisted upon the standard minarets and nimbar recess in the west wall facing Mecca. The dhuni fireplace was an innovation; he apparently regarded this as the ennobling of a faqir observance.

Sai Baba sometimes advocated to Hindus the reading of various sacred texts such as the Eknathi Bhagavat. However, he would not give the formal initiations that some supplicants anticipated. He occasionally recited the first chapter of the Quran. Consisting of seven verses, that chapter is known as Al-Fatihah (“The Opening”).

Dabholkar's book in Marathi gained a foreword by Hari Sitaram Dixit (d.1926). This was the same prominent devotee who ousted Abdul Baba from the role of tomb custodian. Dixit subscribed to an interpretation of the saint that is currently considered idiosyncratic by Sai devotees. He referred to Sai Baba as having been born ayoniya, which literally means without a womb, i.e., without a human mother.

The ayoniya concept avoided the issue of whether the saint was born a Muslim or a Hindu. The innovation was closely linked to an interpretation of divine incarnations in the Hindu tradition, entities who were all considered to be the consequence of a virgin birth. (42)

A realistic alternative, for the biography of Shirdi Sai Baba, is to accommodate both religious orientations (i..e., Muslim and Hindu) in due perspective, duly checking the available sources and contextual details.

9. Upasani Maharaj

Despite the preferential manipulations of context, many Hindus continued to regard Sai Baba as a Muslim. Indeed, Narasimhaswami reacted to the widely emphasised Muslim identity during the early 1930s, not at first wishing to visit Shirdi. Narasimha Iyer, later known as Narasimhaswami (1874-1956), was a brahman of South India who became a lawyer. He subsequently renounced his professional career and opted for a renunciate life. He joined the ashram of Ramana Maharshi, but afterwards moved elsewhere. One interpretation says that he reacted to the Advaita Vedanta of Ramana, which Narasimha found too intellectual for his own disposition. (43)

In 1936, the pilgrim arrived at Shirdi, subsequently to become celebrated as the "apostle of Sai Baba," via his new role as the founder and president of the All India Sai Samaj, based at Madras. By the early 1940s, Narasimhaswami had become the influential populariser of Sai Baba in South India. His “Shirdi revival” quickly spread the fame of the shrine maintained at Shirdi by the Shri Sai Baba Sansthan. His industrious spate of publications assisted the growth of a nationwide Sai Baba movement. However, there is scope for disagreement about a number of his interpretations.

Narasimhaswami notably discountenanced the view, in some Hindu quarters, that Upasani Maharaj (1870-1941) was the successor of Sai Baba. Upasani (Upasni) was also a brahman, having established an ashram at Sakori (Sakuri), a few miles from Shirdi. The intricacies of this situation are complex.

Ironically enough, Narasimhaswami had formerly composed a partisan biography of Upasani. (44) He subsequently fell victim to some strongly circulated rumours about the Sakori guru. The scandal was contrived by influential brahman opponents of Upasani, who were incensed at the importance he gave to a select group of his women disciples. Upasani broke orthodox stigmas by making those women participants in priestly rites and recitation. Upasani dispensed with the primacy of male priests, instead emphasising a return to the Vedic tradition of kanyadin, a word connoting female celibacy and discipline. Upasani even said that women could make more rapid progress in spiritual development than men (he did not mean in all cases, however).

The very conservative libellers accused Upasni of immorality. In reality, the Sakori ashram was a scene of austere discipline. The selected women lived as nuns called kanyas. In later years they emerged victorious from the libels; their leader Godavari Mataji (1914-1990) became famous as a saint in her own right. She and others were able to describe what really happened. Their institution became known as the Kanya Kumari Sthan. By the time of Godavari Mataji's death, there were almost fifty nuns in this community.

Godavari Mataji, Upasani Maharaj |

Upasani Maharaj was similar in some ways to Sai Baba. A vigorous ascetic, he exhibited the same attitude of indifference to physical hardships. Like Sai Baba, he was also eccentric at times, and frequently enigmatic. There was a difference in that Upasani was a brahman, completely unrelated to Islam or Sufism. In his earlier life, he became an ascetic while still in his teens. He subsequently changed to the role of a householder, conducting a professional career in Ayurvedic medicine. When he first heard of Sai Baba, he did not wish to visit the Shirdi saint because of the Muslim identity that was so well known in Maharashtra.

Kashinath Govind Upasani Shastri was born in 1870 at Satana, near Nasik. He was the second son in a family of Maharashtra village priests. His grandfather Gopalrao Shastri was noted for accomplishments as a pundit. Upasani early favoured austerities extolled in the scriptures; he is reported to have adopted Yoga asanas (postures) and pranayama (breath control) in his youth. Upasani appears to have resumed those practices at a later date, after he relinquished his medical career and resorted to pilgrimage with his wife. His reliance upon ascetic exercises then included pranayama, according to one version (Shepherd, Investigating the Sai Baba Movement, pp. 64-5, 189 note 189).

Those exercises, or other dramatic experiences, now resulted in a severe problem: his breathing lost all normal rhythm. Upasni was only able to breathe, though with difficulty, when he massaged his stomach. This precarious condition continually lost the artificially induced rhythm, such as when he tried to sleep or eat. His stomach is reported to have become swollen.

In desperation, the pilgrim Yogi left his seclusion and travelled to Nagpur and Dhulia, searching in vain for a remedy. No doctor knew how to cure him. Upasani became convinced that only another Yogi could help him, one with more knowledge than he himself possessed. He commenced this new quest in April 1911. At Rahuri, he visited a Yogi known as Kulkarni Maharaj. Upasani was disconcerted to find that this practitioner urged him to see Sai Baba of Shirdi, who was here identified as an aulia or Muslim saint. Kulkarni Maharaj reassured his visitor by emphasising that Sai Baba was above caste distinctions. However, Upasani possessed a strong caste pride and persisted in searching for a Hindu mentor.

Upasani subsequently found a degree of relief by drinking only hot water. However, he was in constant fear of a relapse into deficient breathing. He later returned to Kulkarni Maharaj in June. The Yogi again urged him to visit Sai Baba, emphasising that the latter was above creed and caste. This time Upasni acted upon the advice, although still feeling reluctance. He arrived at Shirdi in late June, 1911. His breathing ailment thereafter disappears from the record.

The visitor found that Sai Baba frequently spoke in cryptic language. The enigmatic device muted the religious divide between the Muslim faqir and Hindus. Upasani remained disconcerted by the mosque environment at Shirdi. The visitor intended to leave and return to his wife. However, via a combination of circumstances, he ended up staying at Shirdi (his wife died soon after). His doubts were resolved; he came to view the faqir Sai Baba as the most exceptional entity he had ever met.

Upasani initially stayed with other devotees at Shirdi. Then Sai Baba started to make statements like: "Have nothing to do with them. Your future is excellent; none of the others have such a future." At this juncture, Upasani moved to the far more inhospitable Khandoba temple, inhabited by scorpions. That disused temple was situated on the outskirts of Shirdi, affording a relative degree of seclusion. Khandoba, sometimes described as a form of Shiva, was a popular deity in Maharashtra.

This bizarre phase lasted for a few years; the accompanying interaction with Sai Baba was complex. The liberal Sufi made glowing references to his exceptional Hindu disciple. He enjoined that Upasani was to stay in the derelict temple for a few years, living quietly and "doing nothing." There were no prescriptions for meditation or sadhana (spiritual discipline). The faqir did not sanction exercises like pranayama, an adventure which Upasani did not repeat, knowing too much about hazards that were not generally envisaged by Yoga enthusiasts.

At first the disciple found the changes difficult to accept. He retained his caste complex in matters of food preparation. One day he found that a beggar, a shudra by birth, was hovering nearby while the food was being cooked at the temple. Upasani drove the beggar away with some stern words, a gesture reflecting his brahmanical fear of pollution from lower castes.

When he subsequently took the prepared food to Sai Baba, the old faqir refused to accept the offering and instead drove him away. The disciple believed that Sai Baba was deliberately reflecting his own harsh treatment of the beggar. This event appears to have been the origin of Upasani's subsequent sense of identity with shudras and untouchables (Dalits), an affinity moving at an acute tangent to caste prejudices. "Wherever you may look, I am there." This was one of the allusive statements made to him by the faqir.

Resident devotees became jealous of the temple dweller, who was celebrated by Sai Baba. The situation is generally abbreviated in most reports, indeed to the point of fractional content. Allusive references of the faqir are on record in different languages. "You should not now talk to me, and nor will I talk to you. After four years, you will have the full grace of Khandoba." Upon request, Upasani stopped visiting Sai Baba at the mosque. However, their contact did not cease. There were a number of occasions when Upasani adroitly approached the faqir during the Lendi excursion. Cryptic reassurances were expressed by Sai Baba.

For Upasani, the householder caste life was over. He gained visions and experiences which he later described in fragments. He became averse to food, which he would throw away to dogs. He had no money left, his clothes were now rags. At the mosque, the faqir commented: "Everything I have has been passed to him (Upasani)." Such remarks were puzzling to devotees, some of whom refused to accept the implications. Upasani had nothing. How could he have so much?

Upasani stopped eating, reportedly for a whole year and more. Losing much weight, he became very thin. During that same phase however, he was intent upon performing hard manual labour; his activities extended to making roads and ploughing fields. He would now associate with untouchables and common labourers. He had lost all caste pride. This development was an extension of "doing nothing," a feat which entailed no obvious religious significance.

To some observers, he seemed crazy, no longer the decorous brahman. He lived with snakes and scorpions in the derelict temple, and once embraced a dead horse. Upasani was mocked by local youths and a cantankerous holy man, the latter being a devotee of Sai Baba. Some devotees remained incurably jealous. The situation of animosity increased when, in the summer of 1913, Sai Baba instructed devotees to worship Upasani at the Khandoba temple in the same manner that he (Sai Baba) was worshipped at the Shirdi mosque.

Upasani Maharaj |

Two medical doctors subsequently persuaded Upasani to leave the temple; he was in need of medical assistance after his severe abstinence. These men also wished to stop the harassment in evidence. During 1914, and in the company of a medic, Upasani left Shirdi, subsequently resuming a normal intake of food. He returned to the Khandoba temple over a year later, still meeting opposition from his detractors. Meanwhile, he gained many new devotees at Kharagpur and elsewhere, also living in a bhangi (or Dalit) colony. Upasani undertook further sojourns at the Khandoba temple, largely forgotten in Shirdi devotee annals. Nevertheless, a surprising amount of detail is on record for these years.

Upasani finally settled on the outskirts of Sakori village in 1918. His simple formative ashram was at first an uninviting prospect. However, he gained many followers. These converts included the learned Bapusaheb Jog (d.1926), a former prominent devotee of the deceased Sai Baba. Many brahmans were impressed by the ascetic saintliness and scriptural knowledge of Upasani Maharaj (alias Upasani Baba). He had become very thin during his first sojourn at Khandoba’s temple. He subsequently regained full flesh, appearing in photographs as an ascetic of robust physique.

A distinguishing hallmark was his attire. Upasani did not wear the conventional ochre robe of Hindu sannyasins; he did not take initiation as a swami. Instead he wore a strip of sackcloth (known as gunny cloth) draped over his body. His spartan lifestyle extended to confinement in a “cage” of bamboo bars at Sakori ashram. His austere traditional outlook disliked European cameras; he customarily scowled at the photographers who captured his image.

Upasani made efforts to accommodate orthodox attitudes of the brahman caste, as reflected in his extant discourses. However, there was an underlying element of nonconformism. He early exhibited a strong sympathy with the untouchables or Dalits, also forming a habit of bathing lepers. Such traits were not typical of Hindu gurus.

He was very unpredictable in temperament. Like Sai Baba, he could express irascible moods when confronted by inappropriate tendencies. Gaining a reputation for leonine strength, he was known to place a pretentious person over his knee, slapping the miscreant like a naughty child. Upasani was six feet tall (or more), with a solid torso.

Upasani Maharaj |

A notable episode occurred at Varanasi (Benares) in 1920, during the sojourn of Upasani in this sacred city. The occasion was a maha-yajna, a fire ritual, climaxing in a feast instigated by Upasani. Thousands of brahmans arrived for the feast. Upasani insisted upon displaying a large painting of Sai Baba, who had died in 1918.

The priests reacted to the painting. Some of them complained that Sai Baba was a Muslim, which meant they could not participate in a feast bearing such outcaste auspices. Upasani did not deny the Muslim identity, and at first tried to reason with the objectors. He was patient for some two hours, maintaining that Sai Baba was above religious distinctions, existing as much for brahmans as for Muslims. He even offered to increase the payment for ritual services of the officiating priests.

His opponents insisted that the painting of the alien saint must be removed. They refused to eat the food provided for them until this removal occurred. Upasani then lost patience, instructing his disciples to give the unwanted food to the poor, who were summoned by banging drums. The objectors then anxiously apologised, realising that they were losing their food and the increase in payment (dakshina) for the officiants amongst them. Too late, Upasani was now refusing to comply. He derided the objectors, asserting that Sai Baba was the real pundit (religious expert), not the formal pundits of Varanasi. Upasani dramatically terminated the assembly. (45)

When in such a mood, Upasani Maharaj could be very forthright. He appears to have demonstrated this tendency when the increasingly famous politician Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) visited him at Sakori during the 1920s. Gandhi apparently wished to gain the blessing of the sackcloth saint. There are different versions of the event; some caution is required. Upasani is reported to have said; "You may be a great man, but what is that to me?" (46)

The most obvious conclusion is that Upasani did not want any political involvement such as Gandhi represented. On his own part, Gandhi later complained to the Irani mystic Meher Baba that he could not understand Upasani. The silent Meher Baba was rather more amiable in temperament, treating Gandhi in a disarming manner. However, the Irani asserted that Upasani was a genuine sadguru (spiritual master).

Some analysts have concluded that Upasani Maharaj is the most under-rated Hindu guru of the twentieth century. The full details about him, largely obscured, testify to an entity more interesting (and potentially more significant) than many of those who gained fame in the ashram publicity strategies extending to Western countries. Upasani was not a commercial guru, nor a copyist.

10. Meher Baba

Meher Baba (1894-1969) was one of the two major disciples of Upasani Maharaj (though not recognised by Sakori ashram, who have demonstrated a Hindu caste cordon against Zoroastrians appearing in the biography of Upasani). Meher Baba was neither Muslim nor Hindu, but an Irani Zoroastrian. Born Merwan Sheriar Irani, his biography is far more detailed than that of Sai Baba, or even Upasani Maharaj. His parents came from the severely repressed Zoroastrian minority in Iran. His father was Sheriar Mundegar Irani. Reared at Poona (Pune), Merwan attended the Deccan College, having a talent for English literature. A spiritual experience then dramatically altered his horizons.

Afterwards Merwan personally encountered Sai Baba in 1915 on a visit to Shirdi. He subsequently became a disciple of Upasani Maharaj, visiting Sakori ashram from the inception, even being present at the abovementioned maha-yajna at Varanasi. Merwan Irani was also closely involved with the distinctive figure of Hazrat Babajan (d.1931), the female Muslim faqir who became renowned at Poona.

Hazrat Babajan, Meher Baba |

The copious literature on Meher Baba includes important significators to both Upasani Maharaj and Sai Baba. Meher Baba and some of his disciples knew a great deal about Upasani. Gustad Hansotia, a Parsi Zoroastrian, was originally a devotee of Sai Baba before transferring to Upasani (and later Meher Baba) when the Shirdi faqir died.

Some brahman devotees of Upasani stigmatised Meher Baba as an outcaste intruder at the Sakori ashram. He was unwelcome, both as a Zoroastrian and as a favoured disciple of the brahman guru. The jealousy arising in his direction is reminiscent of the rather similar situation afflicting Upasani at Shirdi several years earlier. Meher Baba moved on to other locales, arriving in 1923 at a site a few miles south of Ahmednagar. That desolate and very inhospitable environment was a disused military camp of the British, adjoining the village of Arangaon. Two years later, this site became Meherabad ashram, the eventual setting for the tomb of Meher Baba many years afterwards. Meherabad was in the same zone of Maharashtra as Shirdi and Sakori, though further south of those two villages.

At Meherabad, the disciple of Babajan and Upasani created a hospital and a school for boys and girls, also commencing an activity of personally ministering to the poor. He gave close attention in varied ways to the local untouchables (Dalits) of Arangaon. However, perhaps the most singular event occurred on July 10, 1925, when the Irani ascetic commenced strict silence, which he maintained until the end of his life. He became dexterous at using an English alphabet board for communication.

Meher Baba's sympathy for the Indian untouchables (Dalits) emerged strongly at Meherabad. In 1932, he gained a significant (and completely unpublicised) interview with the Dalit leader Dr. Bhimrao R. Ambedkar. Unlike many gurus, Meher Baba would not compromise with caste stigmas or the elevation of ritualism. Caste was eliminated at his ashram.

A commercial writer who proved insensitive to various aspects of Meher Baba's background was the British occultist Paul Brunton (1898-1981), who visited Meherabad in 1930. He included misleading information in a popular book entitled A Search in Secret India (1934). Brunton here snubs Meher Baba as a “Parsee messiah,” instead preferring the Hindu sage Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950). The narrative is deceptive, and not merely because the British writer gives a chronically inaccurate description of the Irani’s physiognomy.

Brunton failed to disclose that he was initially a follower of Meher Baba, and moreover, one who claimed telepathic experiences in this direction. Indeed, Brunton exercised such a strong interest in Meher Baba that he was acclaimed by the Saidapet ashram at Madras, where he gave a talk in December 1930. This ashram was affiliated to Meher Baba, being run by well-educated Hindu devotees, who explicitly acknowledged Brunton as "the founder of the Meher League in England" (the League had been created by the Saidapet ashram, not by Meher Baba). The documentation attests that Brunton was intending to further the League when he returned to Britain.

The conclusion is pressing that Brunton subsequently felt thwarted because his expectations were not fulfilled. His report of a subsequent sojourn, at Meher Baba’s Nasik ashram in February 1931, is substantially misleading. The subsequent British biographer of Meher Baba, namely Charles B. Purdom, states that when Brunton, “then known as Raphael Hirsch, came to see me in London some time after his visit (to Meher Baba), he said he had no doubt Baba was false, as he, Raphael Hirsch, had asked him to perform a miracle but Baba could not." (47)

l to r: Meher Baba, Paul Brunton |

Meher Baba was notably averse to the desire of devotees and “seekers” for miracles. He evidently regarded that disposition as a psychological failing; he would sometimes shock this tendency, and at other times ignore it.

The loss of context in Brunton's Secret India is very pronounced. Various ingredients are very suspect; some reported statements do not tally with other accounts of Meher Baba idioms. The clear intention of Brunton was to make the Irani mystic look a fool for making extravagant claims. Meher Baba did occasionally make private statements about his "spiritual work" that can sound fantastic. However, the generally misleading context contrived by Brunton is underhand, involving the omission of crucial details.

Brunton shows only a very superficial acquaintance with his subject. He even derides the robe of Meher Baba in terms of "looks ludicrously like an old-fashioned English nightshirt." (48) That long white robe was certainly a different auspice to the ochre robe of Hindu holy men, who were a far more common sight. Meher Baba never wore ochre, instead favouring a white garment known as sadra (sudrah), related to the sacred vest or shirt of Zoroastrian apparel. This garment did not in fact match English nightshirts, being rather more reminiscent of the white kafni worn by Muslim ascetics like Shirdi Sai. The relatively unfamiliar Zoroastrian context needs emphasising.

The distortions and pique of Paul Brunton were strangely influential. Many readers of his commercial book appear to have believed every word he wrote. He followed up with a string of bestselling “esoteric” books, eventually adding to his public profile the description of himself as Dr. Paul Brunton. He is on record as explicitly claiming the Ph.D. credential from Roosevelt University in Chicago.

A disillusioned academic partisan discovered that the doctoral credential was fraudulent, amounting to a deception in university terms (in reality, the elevated Dr. Brunton gained a misleading commercial "degree" via a predatory correspondence school that was obliged to close down). Dr. Jeffrey Masson also referred to the nebulous Astral University, one of the fantasies in which Brunton indulged. (49) Some parties continued to advertise the bogus doctoral credential, including the publisher Rider & Company. Brunton's followers regard him as a spiritual teacher and extol The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, a multi-volume work.

There is a pronounced irony in the situation concerning Ramana Maharshi. While Brunton chose to proclaim the merits of the Arunachala sage, no less a writer than B. V. Narasimhaswami (1874-1956) was moving in the direction of Meher Baba. Narasimhaswami composed the first biography of Ramana, having lived at Ramanashram as a disciple. This book was Self-Realization (1931), widely read in later editions. Meher Baba is known to have expressed respect for Ramana as a saintly person; however, these two never met.

Advaita Vedanta proved problematic for Narasimhaswami. Ramana reportedly told him: "I am not your guru." After three years, in 1929, Narasimhaswami left Ramanashram. In 1933, he sojourned at the Kedgaon ashram of Narayan Maharaj (d.1945), where he learned of Meher Baba. He now desired to become the disciple of Meher Baba, and to write the latter's biography. Narasimhaswami visited Meherabad at the end of 1933, where Meher Baba was living in seclusion. The visitor apparently stayed for several weeks (details require confirmation; about seventy followers were staying with Meher Baba at Meherabad in December 1933, see LM:1844). However, events did not occur as Narasimhaswami anticipated. The Irani mystic was not enthusiastic about accepting the new candidate as a disciple. The host reportedly told the visitor: "I am not your guru."

Narasimhaswami is said to have been very upset when Meher Baba told him not to write a biography. The visitor is known to have made a close study of the Irani mystic's life and teaching. He evidently did not want to leave Meherabad, only doing so because Meher Baba suggested that he go to Sakori and write the biography of Upasani Maharaj. (50)

In March 1934, Narasimhaswami accordingly moved on to Sakori ashram, where he became a devotee of Upasani Maharaj, a fellow brahman. He composed a biography of Upasani that was published in 1936. However, that same year he defected, influenced by hostile brahmans who had created adverse rumours. These critics wanted to enforce strict caste attitudes, having reacted to the equality for women favoured by the Sakori guru. Narasimhaswami moved to Shirdi, where he became a follower of the deceased Sai Baba; he was subsequently very influential in the "Shirdi revival," himself now being regarded as a saint.

Meher Baba, Meherabad 1928; incognito, Delhi 1939 |

Some physical details are now of interest. Meher Baba had auburn hair, indicative of his Irani ethnicity. He wore his hair long in the early years of his career, like a dervish or Yogi; during the 1930s he resorted to a braid, which he subsequently favoured on a permanent basis. Of average height, his cranium was large in proportion to his physique. He did not possess the receding forehead so dubiously described by Paul Brunton. His physique was lean, filling out in his later years. He would probably have lost in a wrestling match with the formidable Upasani Maharaj, but his stamina was pronounced. It is said that only the strongest men in his entourage could maintain the pace he demanded on so many of his laborious journeys in India, which could easily become marathon tests of endurance. Meher Baba was a fast walker and an agile hill climber.

Charles Purdom has left the following firsthand description of the Irani saint, dating to the 1930s:

Baba is a small man, five feet six inches in height, slight in build, with a rather large head or a head that appears to be large, an aquiline nose, and an olive complexion. He is extremely animated, has a mobile face, constantly smiles, and has expressive hands and gestures. He creates the opposite of a sense of remoteness or strangeness, making an immediately friendly appeal to those who meet him. He is indeed disarming in his obvious simplicity, and the atmosphere that surrounds him might be described as that of innocence. He is childlike and mischievous as well as innocent. I discovered, and others have told me, that he is a superb actor with quickly changing moods. (51)

The reference to being mischievous relates to a sense of humour, which was pronounced. This attribute is confirmed by a number of the sources. Although an ascetic entity, Meher Baba was anything but the stereotyped image of the mournful penitent. His fasts and seclusions are perhaps more interesting in view of such factors. He did not encourage asceticism or renunciation in his followers, instead strongly advocating a "be in the world but not of the world" outlook.

The first thirty years of Meher Baba’s ashram career were marked by many incognito journeys, including some to Western countries during the 1930s. In India, he customarily travelled by third class rail, which could frequently prove a difficult experience. (52) He notably demonstrated humanitarian and philanthropic tendencies, personally ministering to lepers and diverse indigents. He had a rather uncommon habit of washing the feet of poor people, also presenting them with a gift of food and clothing (or cloth), and sometimes money. He maintained these traits until the end of his life.

Meher Baba tending the poor, circa 1960 |

In 1936, Meher Baba created at Rahuri (about 30 miles north of Ahmednagar) a settlement for mad people, whom he personally tended. This became known as the Mad Ashram. Every day he would scour the ashram latrine, a task relegated to untouchables or low caste people in many Hindu ashrams. There was no publicity for this distinctive project, which had no economic motive.

The Mad Ashram moved to Meherabad the following year, being the precursor of more specialised activities involving the obscure category defined as mast (God-intoxicated), comprising many Hindu and Muslim specimens on a nationwide basis. The only publicity for this unusual pursuit was a book published in 1948, written by the English medical doctor William Donkin, who personally observed a number of the events described. (53)

l to r: Meher Baba as barber, Rahuri 1936; bathing a leper, Pandharpur 1954 |

The charity for the poor maintained by Meher Baba was frequently anonymous. The selected needy persons were generally given numbered tickets supplying the address and date of the venue. The name of the benefactor was not given; Meher Baba was effectively incognito when he dispensed money or other gifts with his own hands. (54) Unlike certain well known gurus, he did not delegate philanthropic work to devotees, instead performing the task himself.

There was no caste management at his ashrams. Meher Baba supervised everything himself, maintaining a simple routine. He gained a degree of donor funding that enabled him to support various devotees and their families. The ashram devotees were known as mandali, predominantly men but also some women; they wore ordinary clothes, not distinctive regalia. There was no ritualism or initiation.

During the late 1930s, a significant gesture was made by Upasani Maharaj. Via messengers, Upasani repeatedly requested Meher Baba to take over management of Sakori ashram. This tactic effectively dramatised the insular attitude of the existing caste Hindu management towards the Irani disciple. The management had been insisting for many years that Meher Baba was only an ordinary disciple of Upasani, just like them. This relegation was attended by their fear of his (Meher Baba's) resistance to caste ritualism and his known sympathies with the cause of untouchable (Dalits).

The Irani disciple (now quite independent) would not agree to the request of Upasani, complaining at the Hindu ritualism prominent at Sakori, which to him signified caste exclusivism. Meher Baba stated that all the Hindu rituals would have to stop at Sakori if he agreed to the request.

After several years of this unusual and obscure series of communications (ongoing since 1936), Upasani became compliant with the counter request. In 1940, Meher Baba at last agreed to purchase Sakori ashram, on the basis of the exceptional arrangement about eliminating ritualism. However, nothing came of the proposal, which was evidently resisted by prominent Hindu devotees at Sakori.

The last meeting between Meher Baba and Upasani Maharaj occurred in October 1941, at the insistent request of the latter. The venue was a solitary hut at Dahigaon, near Sakori. These two entities had not met for nearly twenty years. The event was unpublicised; only a few persons were present. Upasani died two months later at Sakori.

Meher Baba and Upasani Maharaj, Dahigaon 1941 |

Not until the 1950s did a new attitude emerge at Sakori. This change was brought about by Godavari Mataji, the female disciple of Upasani who had become the recognised spiritual leader of Sakori ashram. Her role was elevated by the management, who were now very disconcerted to discover that she revered Meher Baba.

Godavari prevailed upon the management to allow Meher Baba to visit Sakori, first in 1952 and later in March 1954. Meher Baba proved to be tactful, despite the stigmas aimed at him in the past. He was very appreciative of Godavari Mataji, who also visited Meherabad with some of the other Sakori nuns. Meher Baba subsequently made further visits to Sakori ashram at the intervention of Godavari. (55) A detailed account exists of the visit to Sakori in September 1954.

Meher Baba was markedly universalist in outlook. His early following comprised Hindus, Muslims, and Zoroastrians. He was noted for his disciplined way of life. Despite his lifelong silence commencing in 1925, he communicated fluently via an alphabet board and gesture language. His major book exhibits an unusual format, including many terms drawn from Sufism and Vedanta. He spoke Persian, Urdu, Gujarati, Marathi, and English. He would not identify himself with any one religious or mystical tradition. For such reasons, he has proved difficult to classify. He abundantly demonstrated the religio-mystical syncretism occurring in Maharashtra over the centuries. He made this very explicit in his major work, published in 1955, which incorporated Arabo-Persian and Sanskrit (plus Marathi and Hindi) vocabularies, thus strongly attesting Sufi and Vedantic associations (also bhakti or sant associations via Kabir poetry).

He may be viewed as a successor to some aspects of the legacy associated with the Nizam Shahi kingdom of Ahmednagar, founded in 1494 and surviving into the seventeenth century. That regional dynasty was established by a brahman convert to Islam, namely Ahmed Nizam Shah, who possessed a strong ancestral link with Pathri. The Nizam Shahi dynasty, with their capital at Ahmednagar, exhibited more religious tolerance than many other Muslim rulerships. They were keen to patronise learning, with Persian constituting their official language. The Deccani Urdu dialect was strongly nurtured in this territory, resulting from a combination of Persian, Arabic, and Marathi. (56)

Certain associations with Hinduism are misleading. Meher Baba certainly did integrate some features of Hindu philosophy and terminology. However, he was basically at variance with the caste system, brahmanical ritualism, and diverse trappings believed to represent spirituality. He was known to criticise Vedantic punditry, which so fluently recited scriptures and assumed that numerous renunciates were "knowers of Brahman." Meher Baba himself ministered to sadhus (holy men) in his charitable projects. However, he is reported to have said that such categories are not spiritually advanced (save perhaps in exceptional cases).

The teaching of Meher Baba strongly features reincarnation; the expanded format is difficult to find elsewhere. He applied an intensive emphasis to the Sanskrit word sanskara ("impression"), here meaning an impression in the mind or a binding operative in consciousness. Ritualists and Yogis had used this term differently; Meher Baba is much closer to the latter, though nevertheless distinctive. He discountenanced Yogic exercises, which he viewed as bindings, amounting to a category of impressions (sanskaras) that trap the mind.

He sometimes referred to the situation of Yogis who claim the "stopped state of mind" in meditation. That condition, in which the mind is temporarily suspended, is deceptive. Meher Baba observed that when the meditation ceases, the Yogi is again subject to the complex flow of impressions in the mind. The Yogi has not escaped the sanskaras, which may even intensify.

Meher Baba did not view meditation as an end in itself, maintaining that this common resort cannot achieve what he called "God-realisation." This attainment he depicted as being extremely rare, indeed so rare that a frequent response is incredulity. A reason given is that the impressions in the mind must be completely eliminated for this realisation to occur. The elimination is virtually impossible to achieve, because of the nature of impressions acting on the mind. This perspective is very different to ideas of "self-realisation" generally found in Hinduism and Western "new age" derivatives.

From this angle, the scope for delusion is prodigious amongst enthusiasts of "nondualism" and other mystical concepts. How does anyone break through the dense and subjective net of impressions which determine thoughts and actions? According to Meher Baba, only some of the 56 God-realized entities (living at any one time) are capable of eliminating the binding sanskaras in the mind of a suitably prepared individual. This version may seem exotic or elitist. However, the exacting criteria separate his version quite substantially from both conventional and popular presentations of enlightenment, including the format of Aurobindo Ghose.

The "spiritual hierarchy" theme of Meher Baba has some affinities with the "hierarchy of saints (awliya)" found in Sufism, although the format is different. The five leaders are here described in terms of qutub, an Arabic word meaning "axis" or "pivot." In Sufism, the five are sometimes split into the qutub and four awtad ("pillars"). The Irani exegete included (as an equivalent for qutub) the Hindu term sadguru, which he translated as "perfect master," a nuance intended to distinguish between a proficient grade and lesser roles of guru, yogi, and advaitin (the term "perfect master" is now widespread, and can easily arouse strong criticism, becoming a commercial label designed to impress the gullible).

The teaching of Meher Baba is that of an independent mystic who had no link with organisational groupings associated with Islamic Sufism or Hinduism. His correlation of terminology between the Sufi and Vedantic traditions appears to have been unique. Furthermore, his version of transmigration through the species is explicable from a Darwinian perspective, with the strong qualification that his spiritualised format eschews both Darwinist materialism and the superstitions about retrograde incarnation found in Asiatic religions.

Meher Baba |

During the latter part of his life, from the 1940s, Meher Baba was active at another ashram called Meherazad, to the north of Ahmednagar. That new ashram (near the village of Pimpalgaon) remained secluded, being very different to some of the more prominent institutions of Hindu gurus existing elsewhere. There were no "miracles." Meanwhile, he continued his incognito journeys. He also undertook public darshans on a very intermittent basis. During the 1950s, he made a public claim to be the avatar, a Hindu term meaning a divine incarnation. This proved to be the most controversial aspect of his career.

A motoring accident in 1956 curtailed his movements, leaving him with a damaged hip. In the late 1960s, he became noted for contesting the supposed spiritual validity of drug experiences, a belief which had become fashionable in the West. He was especially concerned to oppose the popular theories about LSD that gained favour amongst the hippy generation.

His tomb (built to his own specification in 1938) exists at Meherabad. This building resembles the Sufi dargahs of the Deccan, though relatively plain and unadorned. (57)

Tomb of Meher Baba, Meherabad Hill |

After his death, the Western followers of Meher Baba (including Pete Townshend) promoted a sentimental devotionalism. Many of them tended to favour simplistic catchphrases like “Don’t worry be happy.” That represented an aside of their figurehead, not his teaching, which remained relatively obscure, like many of the biographical details. See further Sectarian Issue and Oceanic.

11. The Sai Baba Movement at Issue

The close juxtaposition of the abovementioned three saints (or whatever they are diversely called) in Maharashtra has been considered distinctive, and even unique. These three entities (Sai Baba, Upasani Baba, Meher Baba) were significantly interlinked in terms of personal affiliations. Their geographical proximity is relevant. They covered a whole century and three Eastern religions between them, with Christian and other followers being added. The linguistic range encompassed Persian, Urdu, Marathi, Gujarati, Sanskrit, and English.